- The Righteous Movement

- The Righteous Movement

- The Righteous Movement

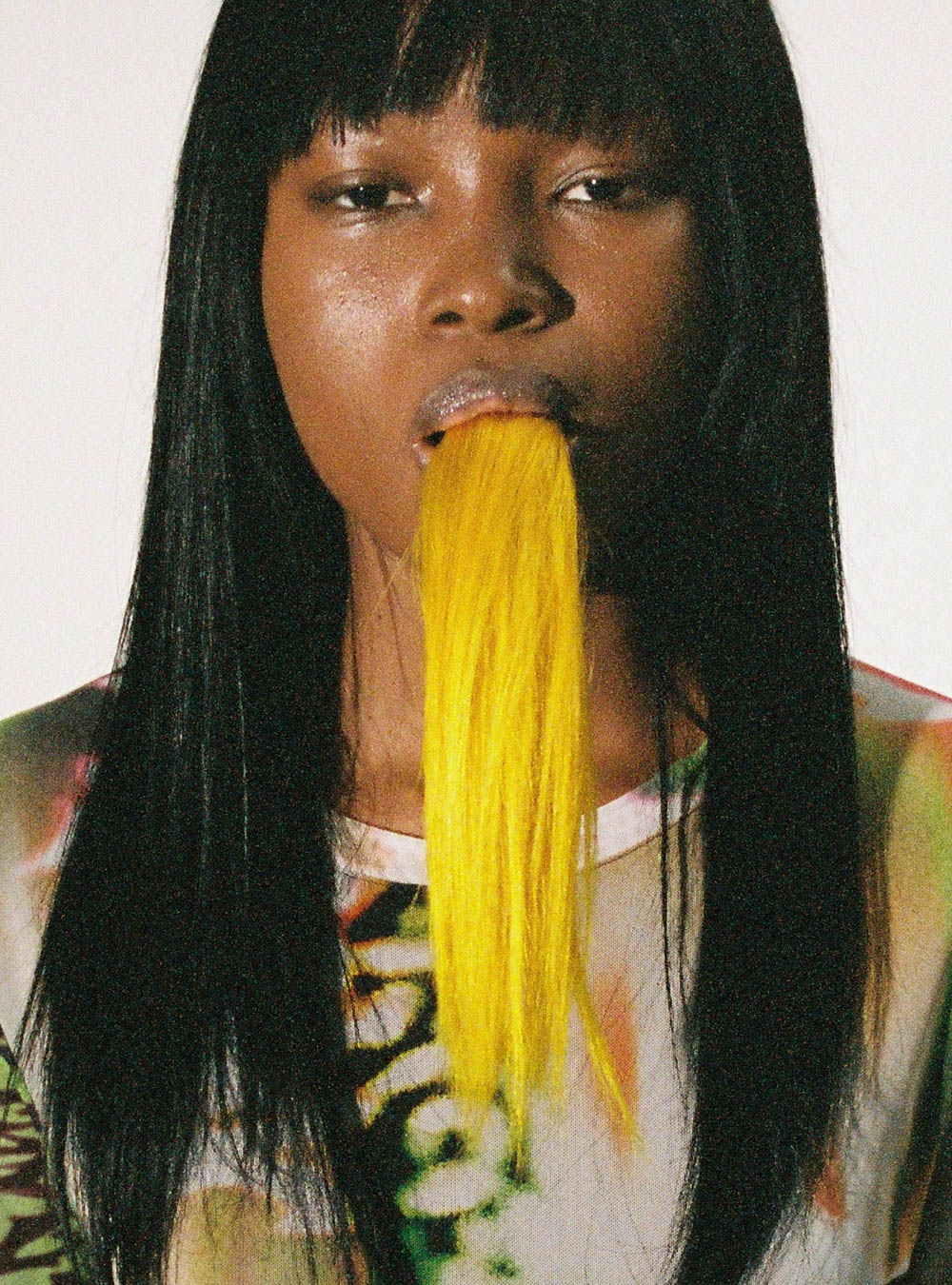

ART+CULTURE: African Rastafarians from the Western Cape share their beliefs and rituals around hair

Film: Michael Lindsay

Words: Katharina Lina + Michael Lindsay

Photography: Thulani Zimu + Anthony Dias

Special Thanks: Christopher Mpotulo, Bongane Bhelu, Zola Booi, Andile Tibane, Odwa Sityeta, Vuyile Somhlahlo

While filming another INFRINGE story in Khayelitsha, South Africa, a Rasta elder, Christopher Mpotulo, took it upon himself to challenge us in the street. After learning that we were sharing stories about hair culture, he felt we needed to understand more about the real importance of hair for Africans and the underlying political and spiritual positioning that was essential to a true and authentic life.

Rastafarianism developed in 1930s Jamaica and is considered both a new religion and a social movement. With ideologies around Afrocentrism and pan-Africanism inspired by activist figures such as Marcus Garvey, Rastafarianism can be seen as a reaction to the historic oppression of black people through the Atlantic trade slave and European imperialism.

In the 1920s Garvey famously prophesied “Look to Africa, when a black king shall be crowned, for the day of deliverance is at hand”. Rastafarians see this prophecy start to be fulfilled when Haile Selassie was inaugurated as King and later Emperor of Ethiopia. Selassie, a proclaimed descendant of the Solomonic dynasty, was considered a prophet of Jah (God), and further fulfilled the prophecy of liberating people of African descent when he gave 500 acres of land to black people from the West who wished to come and settle in Ethiopia, which many Rastas consider to be Zion.

Besides the socio-political notions, and their Biblical interpretations and beliefs, Rastas underline the importance of being spiritually connected to nature as much as possible. As time went on, the decentralised and heterogenous nature of the movement led to varying focal points, with Afrocentrism being put on the back burner for some. As our new-found friends taught us, for them it’s not just about being black and having dreadlocks; you can be bald and be a Rasta, and you can even be white and be a Rasta, as long as you “have faith, connect with nature and are righteous”.

Hair is an extension of an external cultural aspect, as well as an internal identity one. The policing and discriminating of black hair reinforce the discrimination against black people. Dreadlocks are the result of afro hair being in its natural, unadulterated state, which is why they serve as a perfect symbol for protesting against oppressive Eurocentric beauty ideals, unapologetically taking pride in one’s own background, and also living the most natural life possible.

So upon Mpotulo’s invitation, INFRINGE hiked up a mountain in the Western Cape with a group of Rastas from Cape Town to learn of their ritual hair cleansing in the pure water that flows there.

We filmed in a place where access is denied so we have kept the locations undisclosed, but these men take the risk to trespass because this ritual is so important to them.

They feel very deeply that their hair represents their freedom, and is such an integral part of who they are, that it forms an extension of their very being and cleaning their hair in the pure mountain stream water is akin to “cleansing their aura”.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR