- Resistance Through Hair

- Resistance Through Hair

- Resistance Through Hair

ART + CULTURE: Artist Kate Kretz describes how the process of her striking and painstaking human hair embroideries “feels absurd, bordering on insane”

Artwork: Kate Kretz

Photography: Greg Staley

Interview: Katharina Lina

When Ms. Dwyer assigned her AP English class to read the book Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, it was homework for some, and a life changing moment for Kate Kretz. “I went from feeling like a misfit aberration to finding my place in the universe; I’m not a freak, I’m just an artist.” She watches the happenings of her surroundings, uses her brain to digest and her hands to rework headlines of negativity, and ultimately produces pieces of work that are as thought-provoking as they are cathartic.

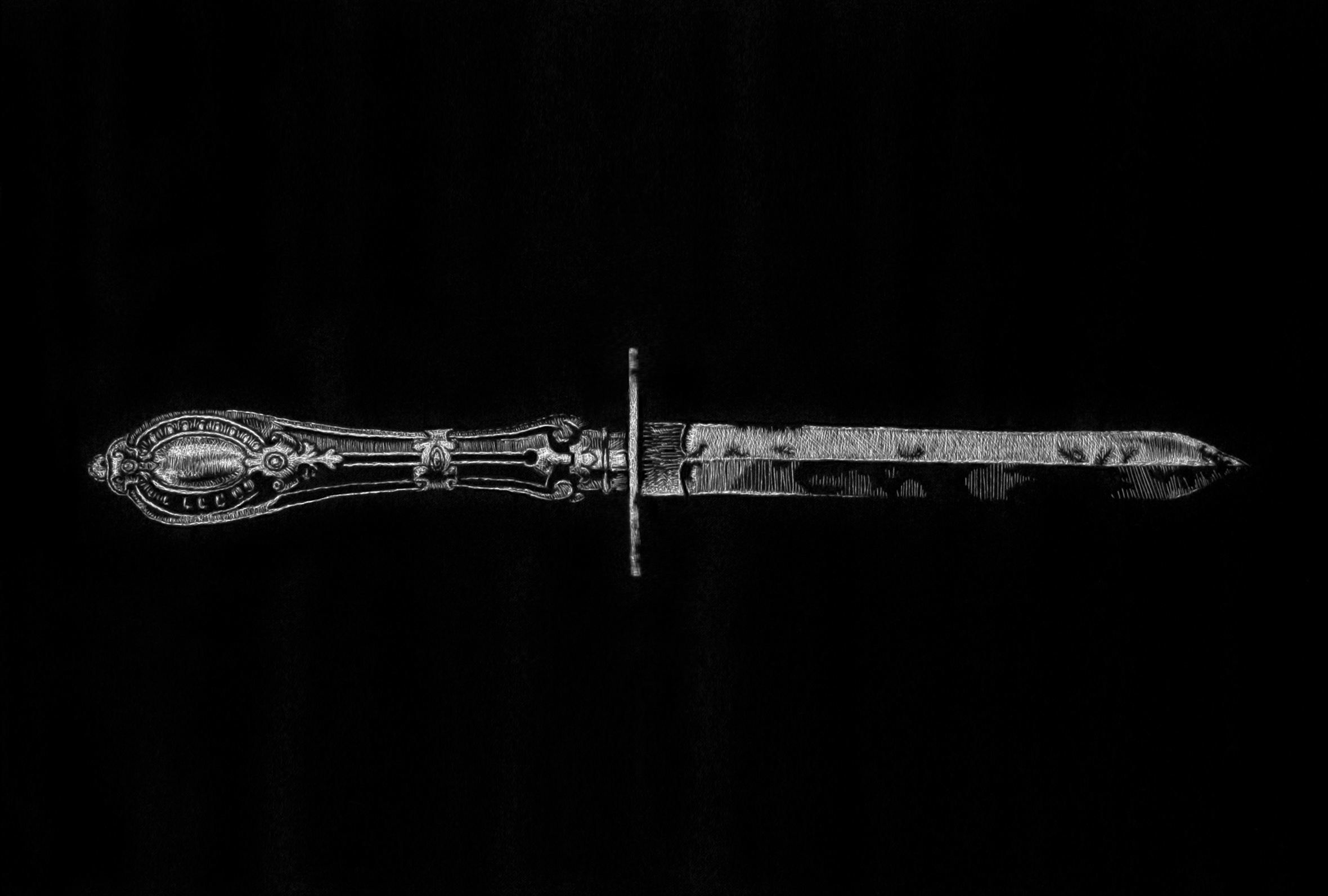

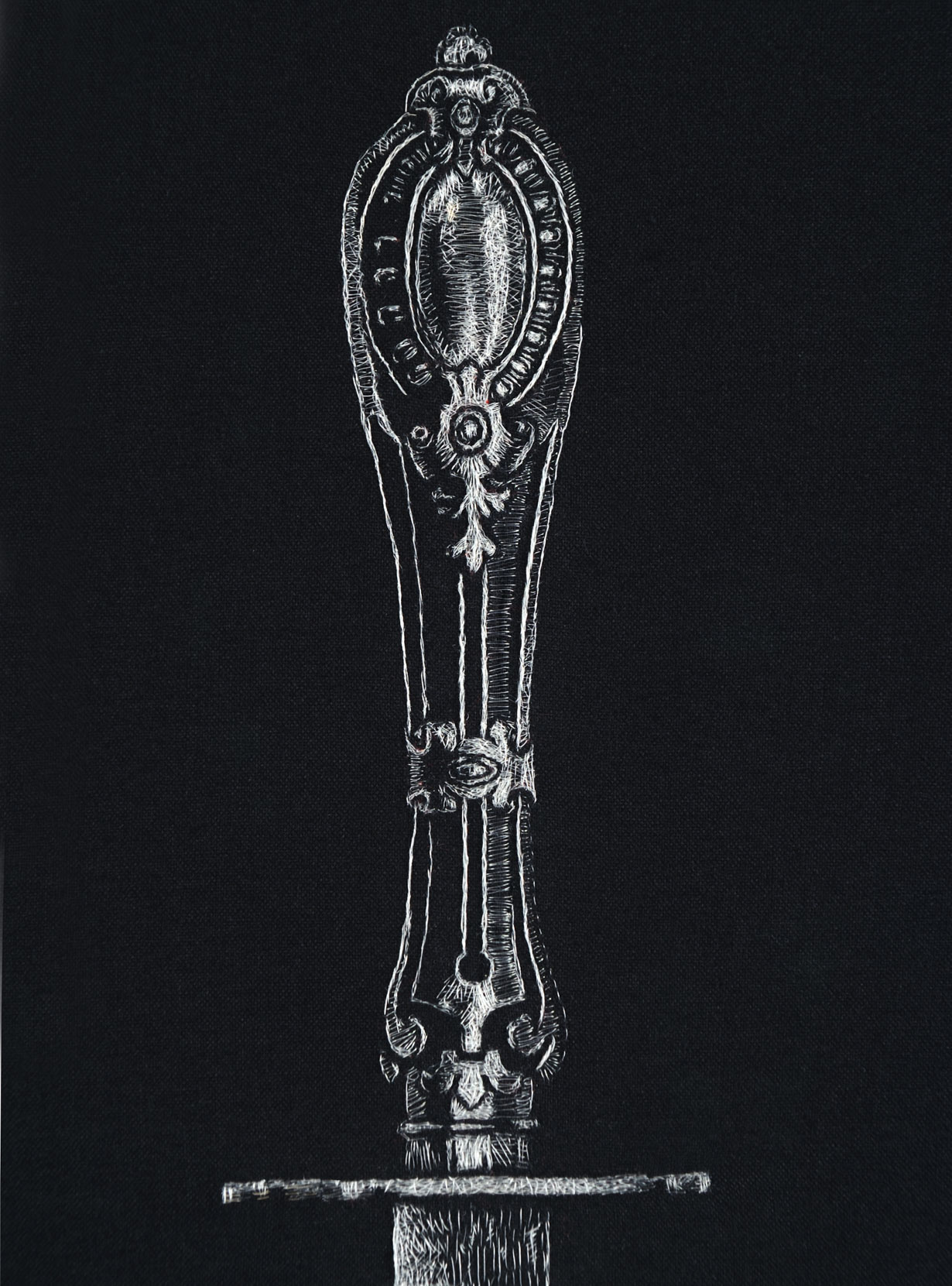

Some of her more controversial works confront America with its gun obsession, and challenge patriarchal violence – much to the distaste of some. Pushing the limits of what people may be comfortable with seeing makes her life much more difficult, she says, “It is harder to find brave venues to show my work, harder to find a gallery to represent me, I get attacked by conservative trolls, and while I get great reviews and occasional grants, I sell very little.” Many of her works Kretz wouldn’t put up in her own house, she says, but that’s precisely it – her works were never supposed to act as pretty décor. “I always envision the work in museums, where people are prepared to think, feel, and be challenged.”

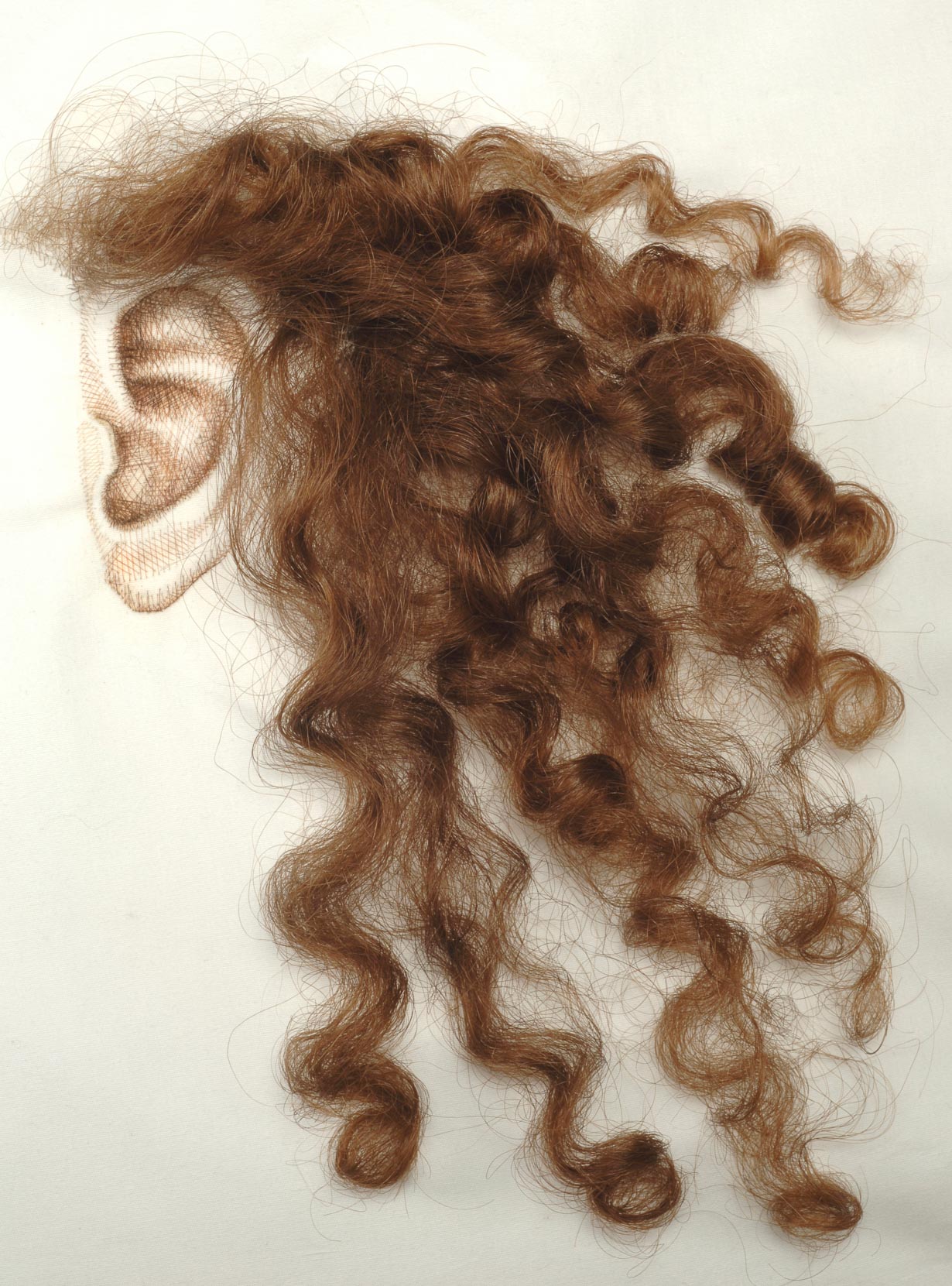

Her works include several human hair embroideries that deal with love, loss, and motherhood. When creating art that dissects human emotions and memories, hair may possibly be the most profound medium. Nothing quite like it exists; a part of the body that holds both genetic and lifestyle information, while also carrying personal sentiment. Although a medium rich in meaning, embroidering with human hair is incredibly tedious work consisting of countless hours of handwork and tying miniscule knots. But this prolonged labour in itself is an act of resistance for Kretz, “I obsess over craft as our world becomes disposable. I wield emotion in its messiness because it’s uncool. I work until my hands shake, because the world does not care.”

“I LOVE my grey hair, and it feels like a big middle finger to our youth-obsessed culture”

You were originally trained in painting, but also use a variety of media. What inspired you to first start working with human hair? When I get an idea for a piece, I always ask myself what medium would make the work most powerful: does this need to be a drawing, or a sculpture, for example? When I initially thought of creating drawings with hair, I was delighted, because, to my mind, this had to be the most potent art medium in the world. Hair is like the rings of a tree, you can ‘read’ what it has recorded, such as changes in diet, pregnancy, stress, illness, etc. I was able to create an object that contains the history of someone’s life within it. There are not many art mediums that measure up to that kind of resonance. I believe that hair holds great power, and many cultures, past and present, agree.

Hair has many faces; sometimes admired for its beauty, while at other times it can elicit disgust. What is your history with your own hair? I have always had thick, long hair that I considered one of my best physical attributes. I was born a brunette, dyed it red in my late 30’s, and decided to stop dyeing to go grey about five years ago. It is still mostly dark, with dramatic white streaks. I LOVE my grey hair, and it feels like a big middle finger to our youth-obsessed culture and the standards dictating that I am supposed to put chemicals on my brain receptacle to remain beautiful.

When I give lectures, people are always asking me how I source the hair because they are grossed out by the thought of it. They think I am pulling it out of the drain or someone’s hairbrush. I began by using my own hair, running my fingers through it right after I had shampooed and sticking it in a baggie. I later purchased human hair because I wanted more colour variations. For the last decade, what is most important to me about the hair is the history of its owner and what is recorded in the hair.

The piece “My Young Lover” is a bit different in its conceptual origin. In my 30’s, I dated a musician who was much younger than I. For years, I had been drawn to painting people who had Pre-Raphaelite hair (long ringlets), and while this guy had other lovely attributes, I would be lying if I said that his long golden curls were not part of the attraction. One day, he brought me his hair in a box, stating that he thought I loved his hair more than I loved him. I kept the hair in a glass box for many years until I met my husband, then I decided that it would be bad juju for me to have it in our house, so I made an artwork with the hair. The piece was inspired by Leonard Cohen lyrics “I loved you in the morning, our kisses deep and warm, your hair upon the pillow like a sleepy golden storm…” I had to put a drop of archival glue on the end of each strand of hair, then I invented a tool to thread it through the pillow so it would look like it was growing out of the pillowcase. The piece was in the Pricked: Extreme Embroidery show at The Museum of Arts & Design in NYC, and was chosen by the curator to be the image that would be on all the PR, posters, and the banners lining the streets. It would have meant a lot for my career. But the curator’s choice was nixed; some people thought it was “too creepy”, so a happier work was chosen.

“I obsess over craft as our world becomes disposable. I wield emotion in its messiness because it’s uncool. I work until my hands shake, because the world does not care.”

I imagine hair is much stiffer than ordinary embroidery threads, which must make the process much harder. What is your method for embroidering with human hair? I often say that my works are not “embroidered” in the conventional sense of the word, they are wrought: these pieces take 3-9 months to create, are sewn at the rate of 3 hairs an hour. The process feels absurd, bordering on insane. I have read how other people found simpler ways to do it: they tie many hairs together end to end, or embroider with several hairs at a time, but I need more control in my work. I tie a knot in the end of one hair, embroider with it, then tie a knot at the other end, the way that most people work with thread. The hairs often break, and they are thinner at one end than the other. Hair as a medium is slippery, springy, and it responds to temperature and humidity, so it expands and contracts.

Could you talk about how you sourced the grey hair for Rupture? Rupture is embroidered with the hair of those who have experienced a profound loss. The seismic shift, the ‘before’ and ‘after’ this life-transforming moment in their personal narrative, is literally embedded in the threads. I crowdsourced the hair from friends, and friends of friends on Facebook. Some people shared their stories with me, and others just sent the hair. This piece gains enormous potency from the accumulated depth of grief from many people: when I look at it, I see a silent, collective wail of pain.

In Rupture, hair carried the memory of loss, in your Motherhood series, it seems to be a feeling of protectiveness and worry. How can “dead” hair translate human feelings and emotions so clearly? To begin with, art (especially laborious, time-consuming art) is, in part, about marking time and harvesting value from that time. You make this tangible object, imbued with meaning from all the invested hours, effort, and intentions you held while making the piece. Hair embroidery is a much more intense process than most other types of art making, and then you have time recorded in the material itself. More importantly, hair has its own intrinsic meaning. The reason that people are so grossed out by seeing hair detached from the body is because it functions as a memento mori, a reminder that we ourselves will die. Because hair remains stable and lasts so much longer than the rest of our bodies, since the middle ages, people of various cultures have been keeping the hair of loved ones as a last remaining souvenir for private mourning purposes. During the process of mourning, the sense of a loved one’s absence is so tangible, that having something physical from the deceased that one can still actually hold on to is a powerful tool to help with this life transition.

In a similar way, I made all this work with the hair that was on my head when I was carrying my daughter. It marks a time when she was inside my body, when I was dreaming of who she would be. That time will never come again: it was sacred. We were bound together then, and now that connection in the form of hair sewn onto one of her baby dresses continues to bind us.

Are you planning on creating more works with human hair? I am not sure that there will be any more of the elaborate, drawing-like embroideries. I have always known that my body was only capable of producing so many of these pieces: each one feels like it takes years off my life. One should never say never, but the concept for a new piece would have to be pretty important for me to commit to the pain and intensity of making it. That said, I know that I will make more work with hair, I just have no idea what it will look like. It is always fascinating to me to push the boundaries of materials, make them do things people could not previously imagine. When I was younger, I piloted planes and loved to skydive: now I derive the same kind of thrill-seeking from my work. Starting a new piece, having no idea whether what you are trying to do is even possible, and then succeeding? Nothing is better than that.

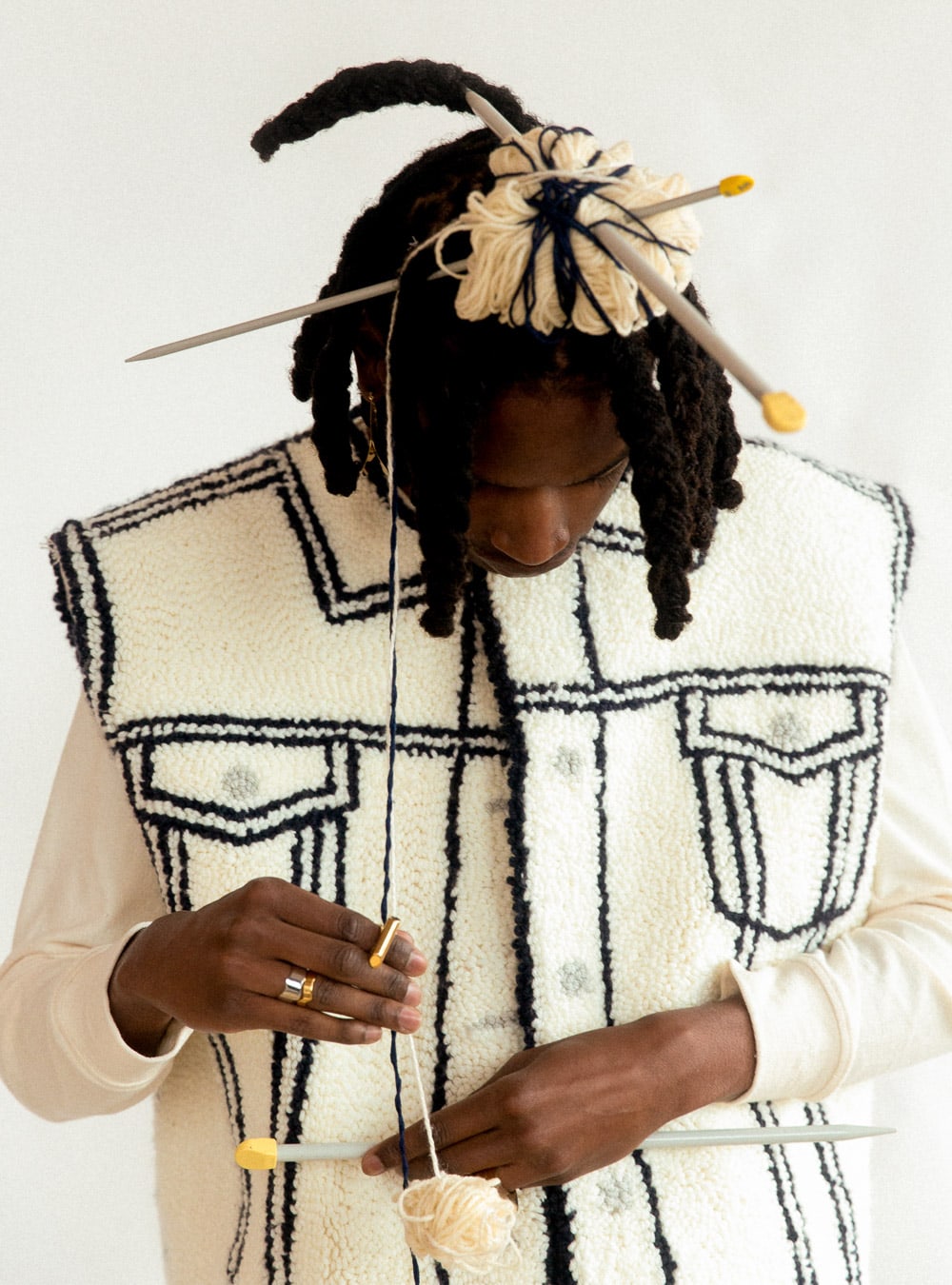

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR