- Material Gains

- Material Gains

- Material Gains

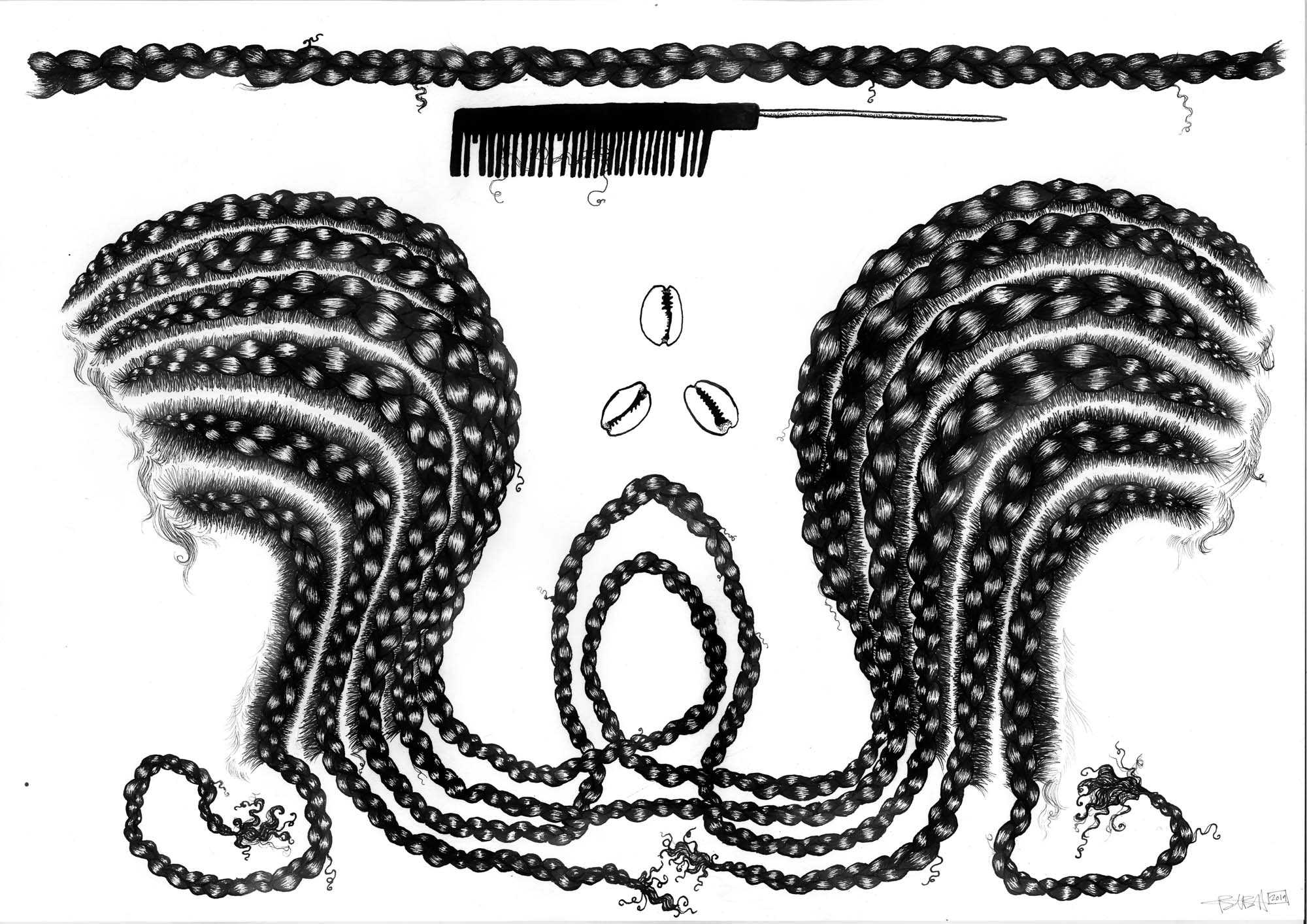

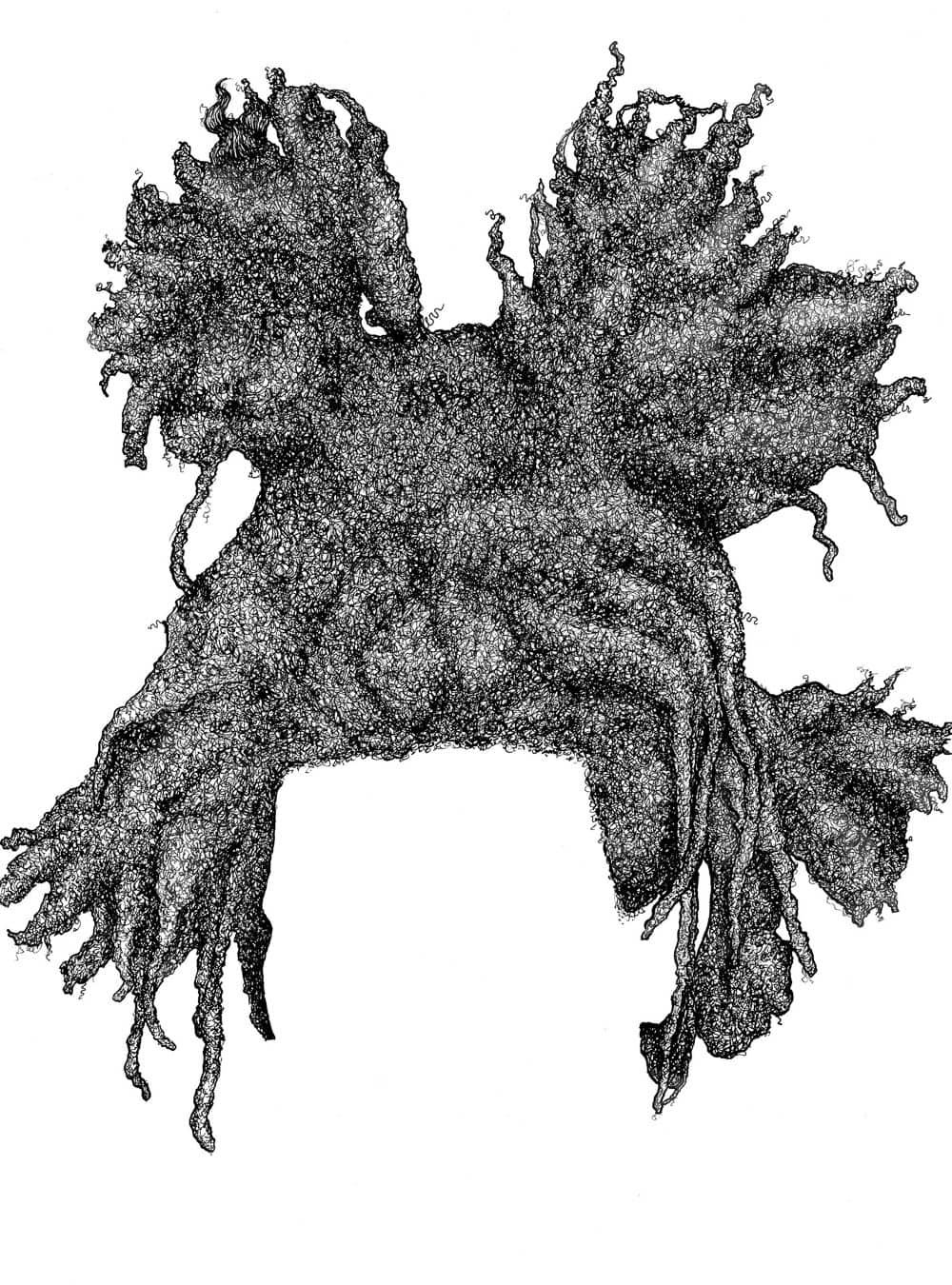

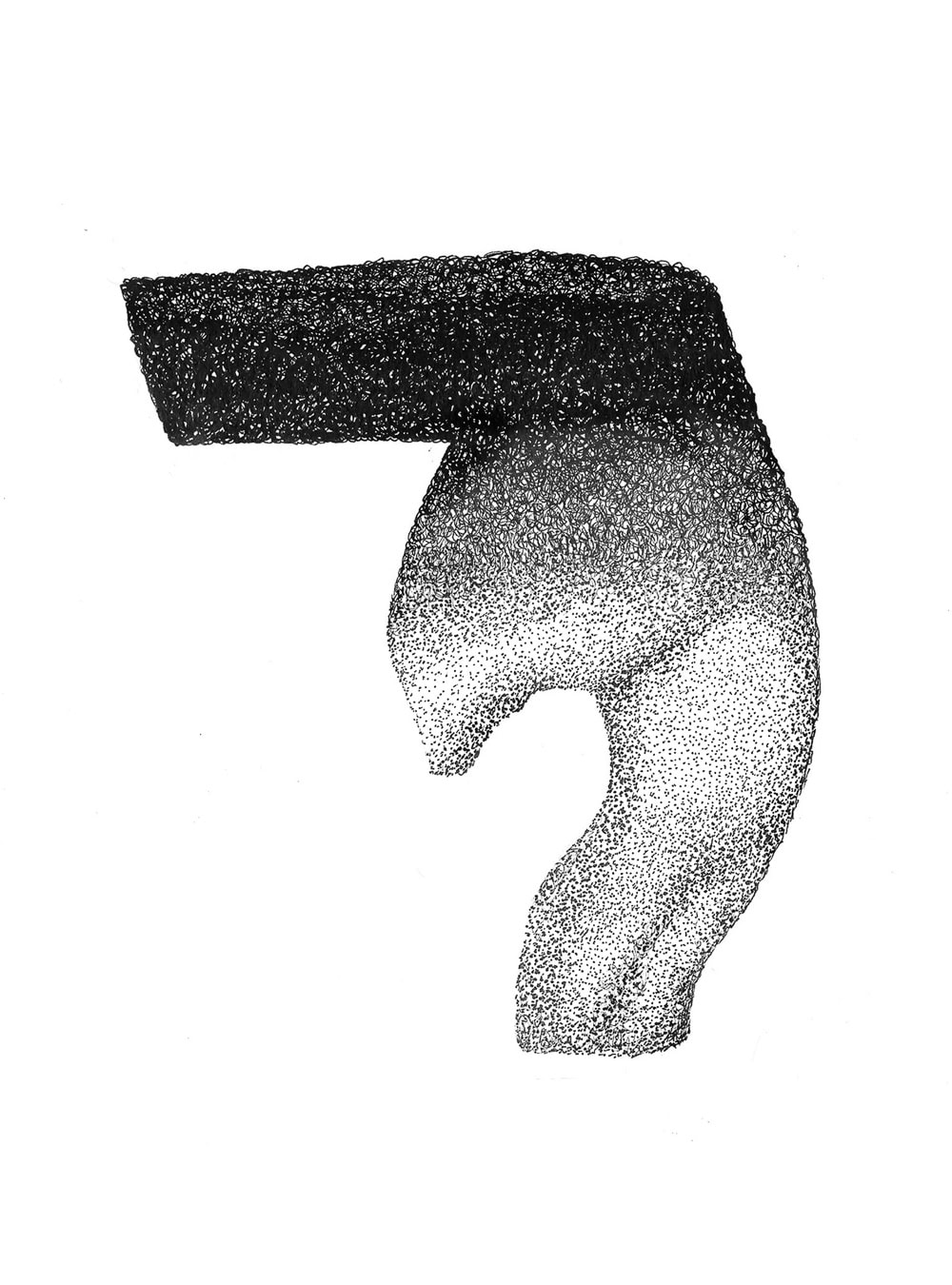

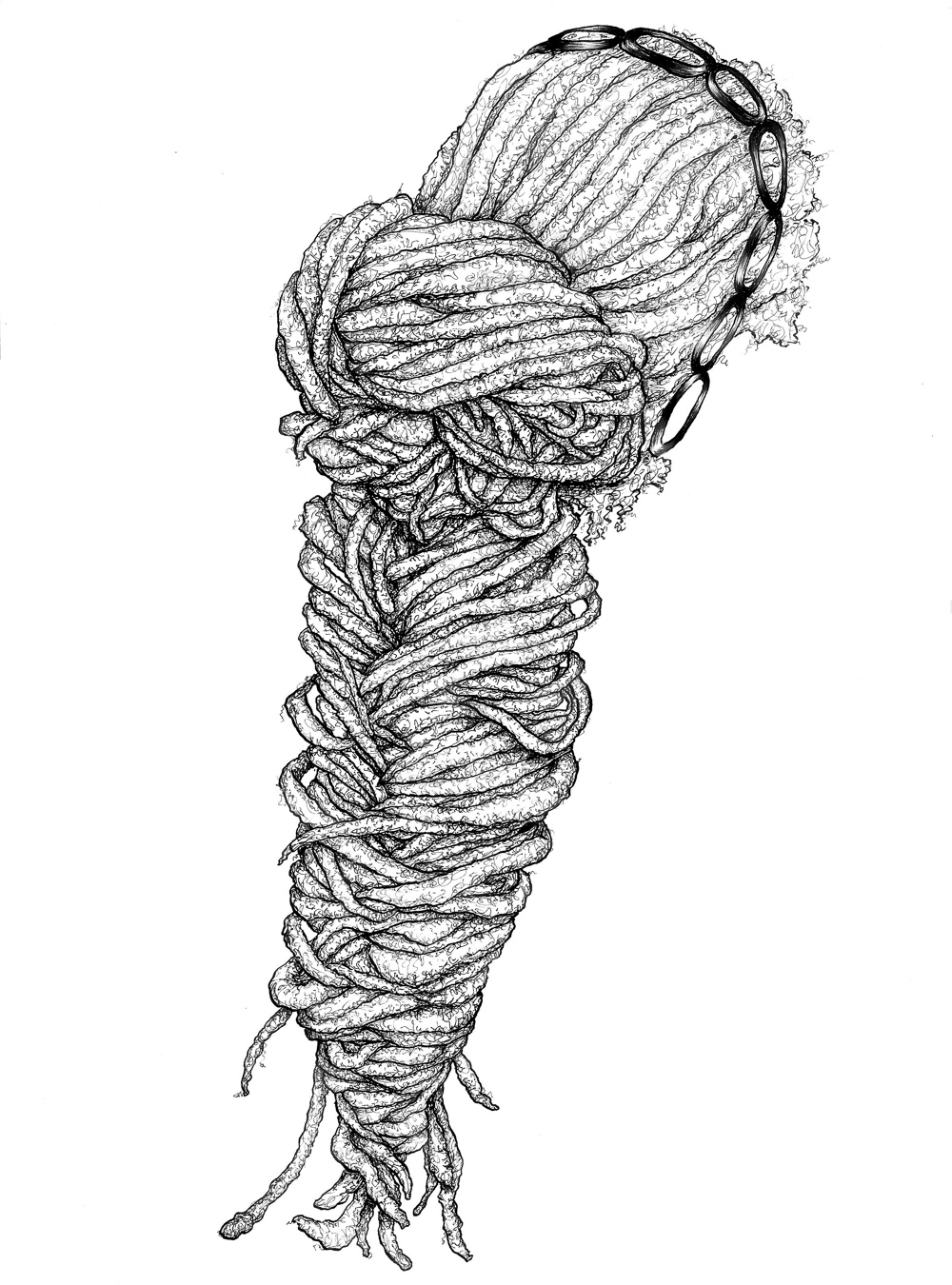

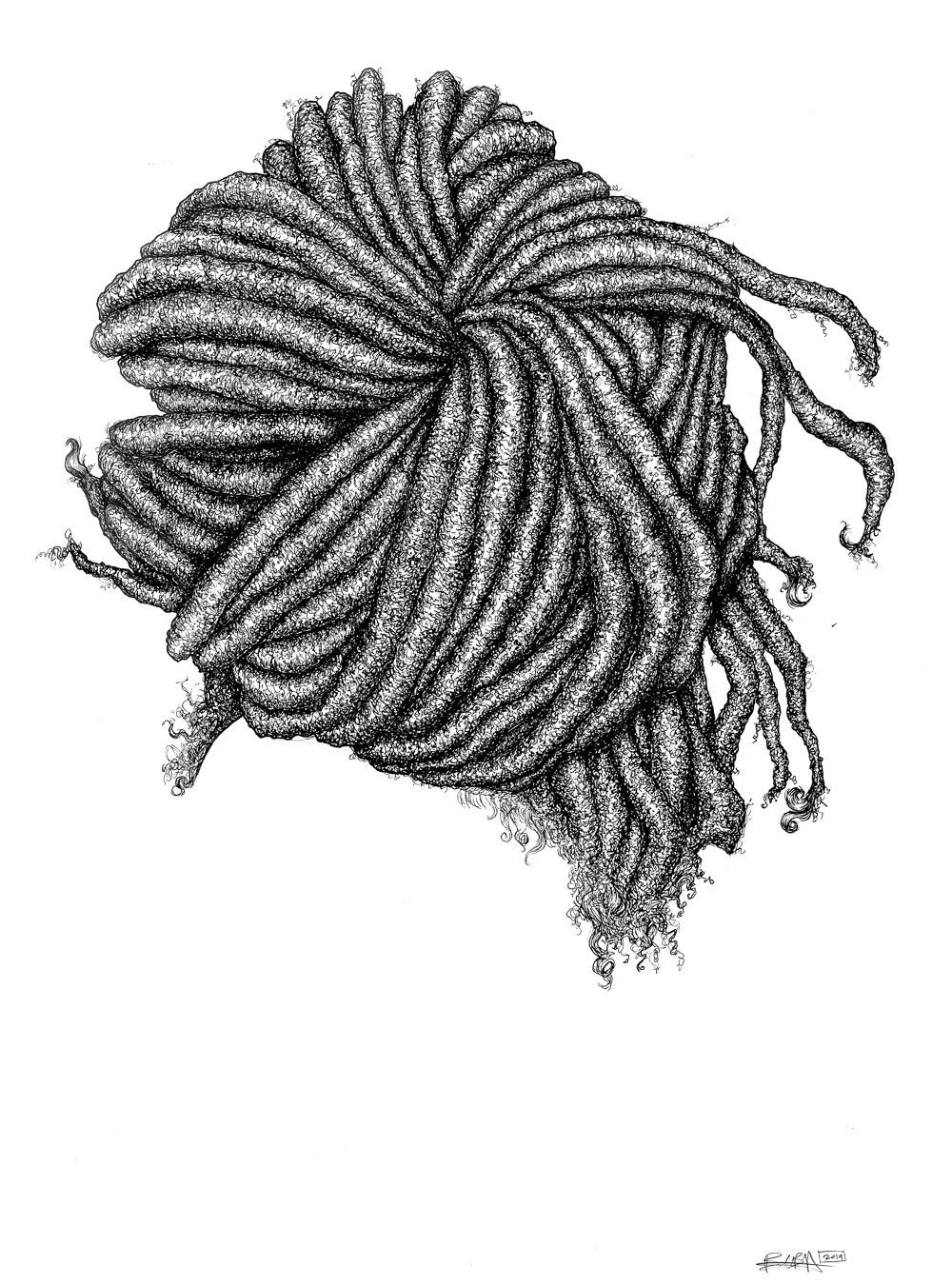

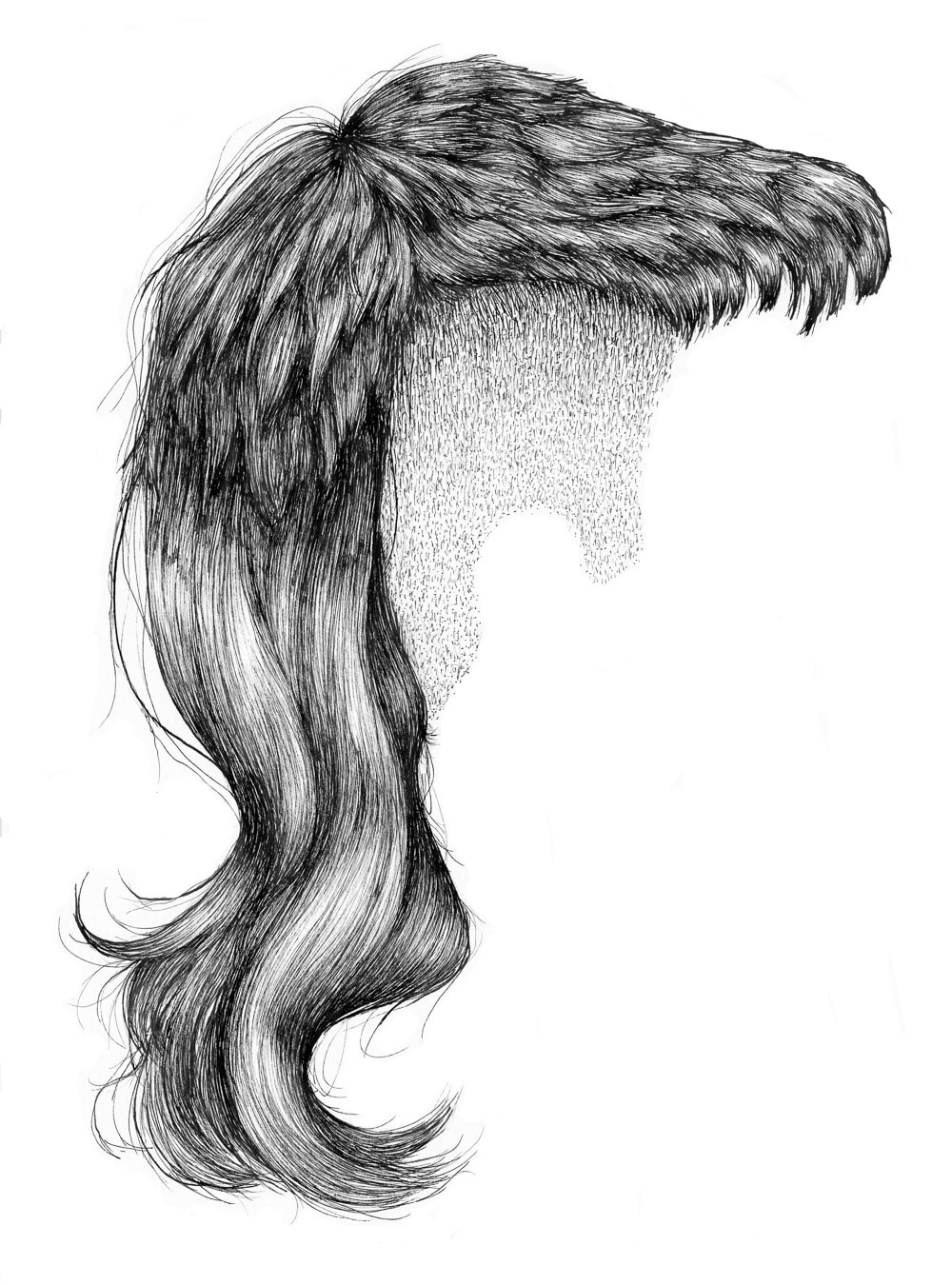

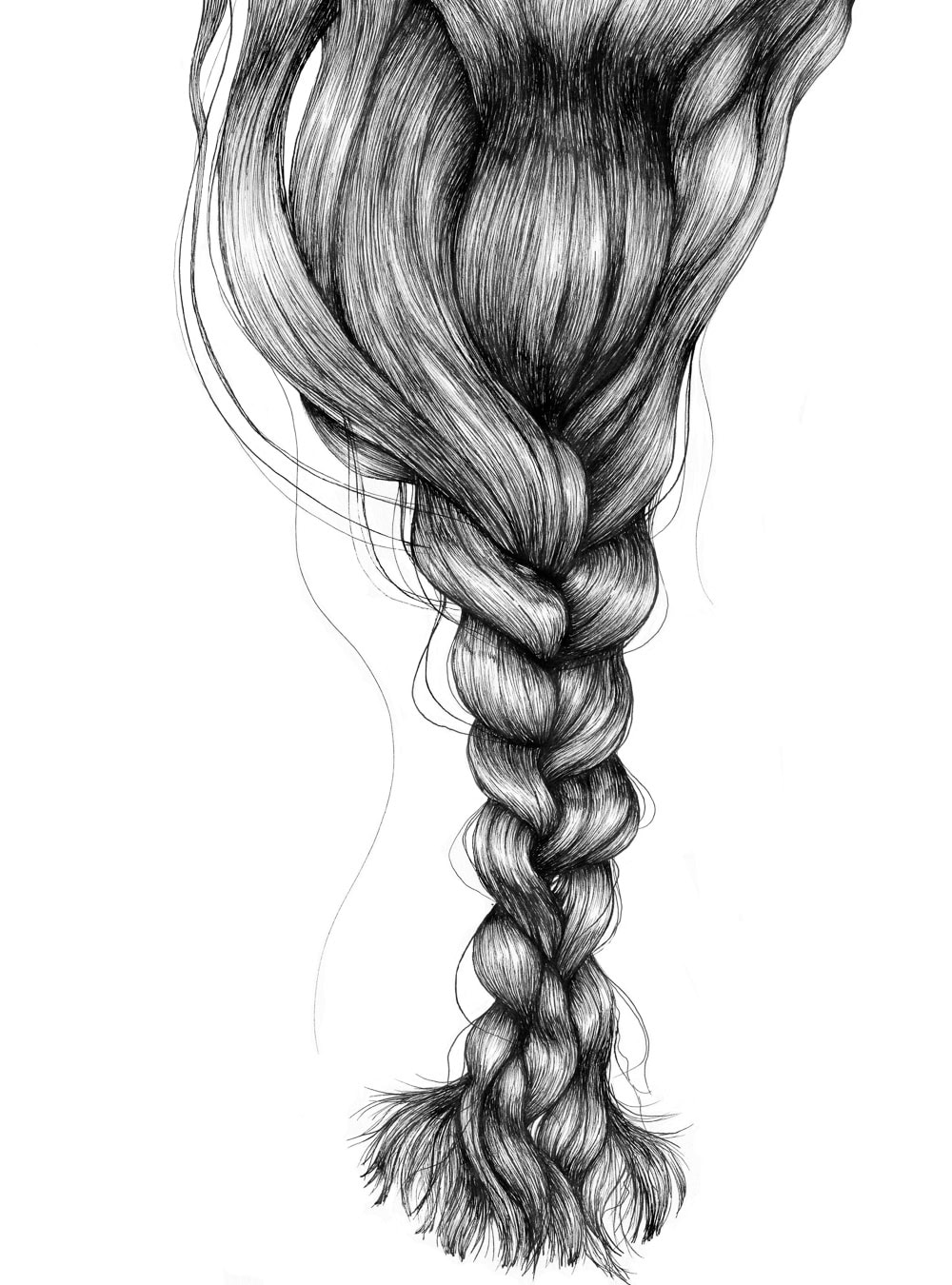

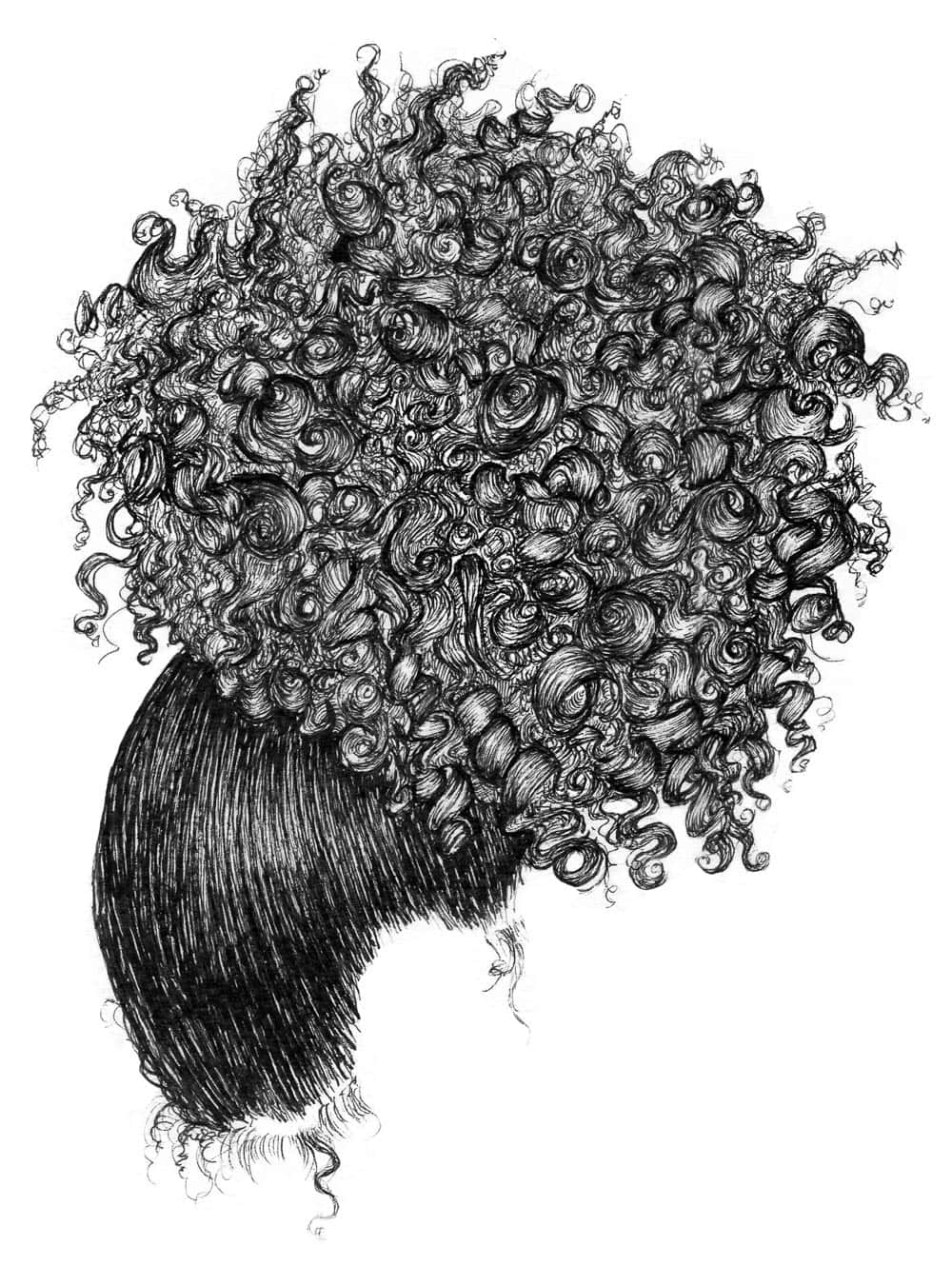

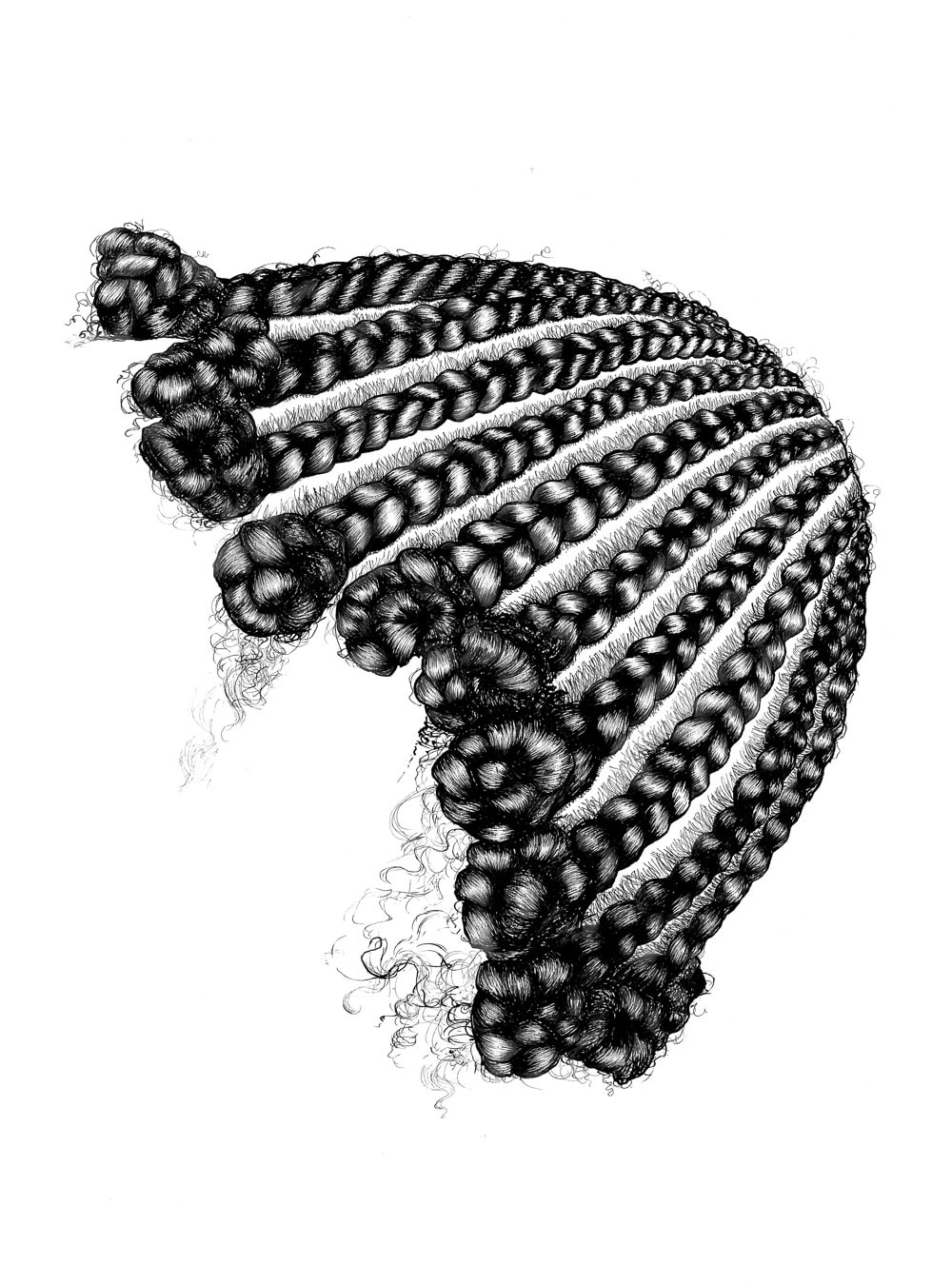

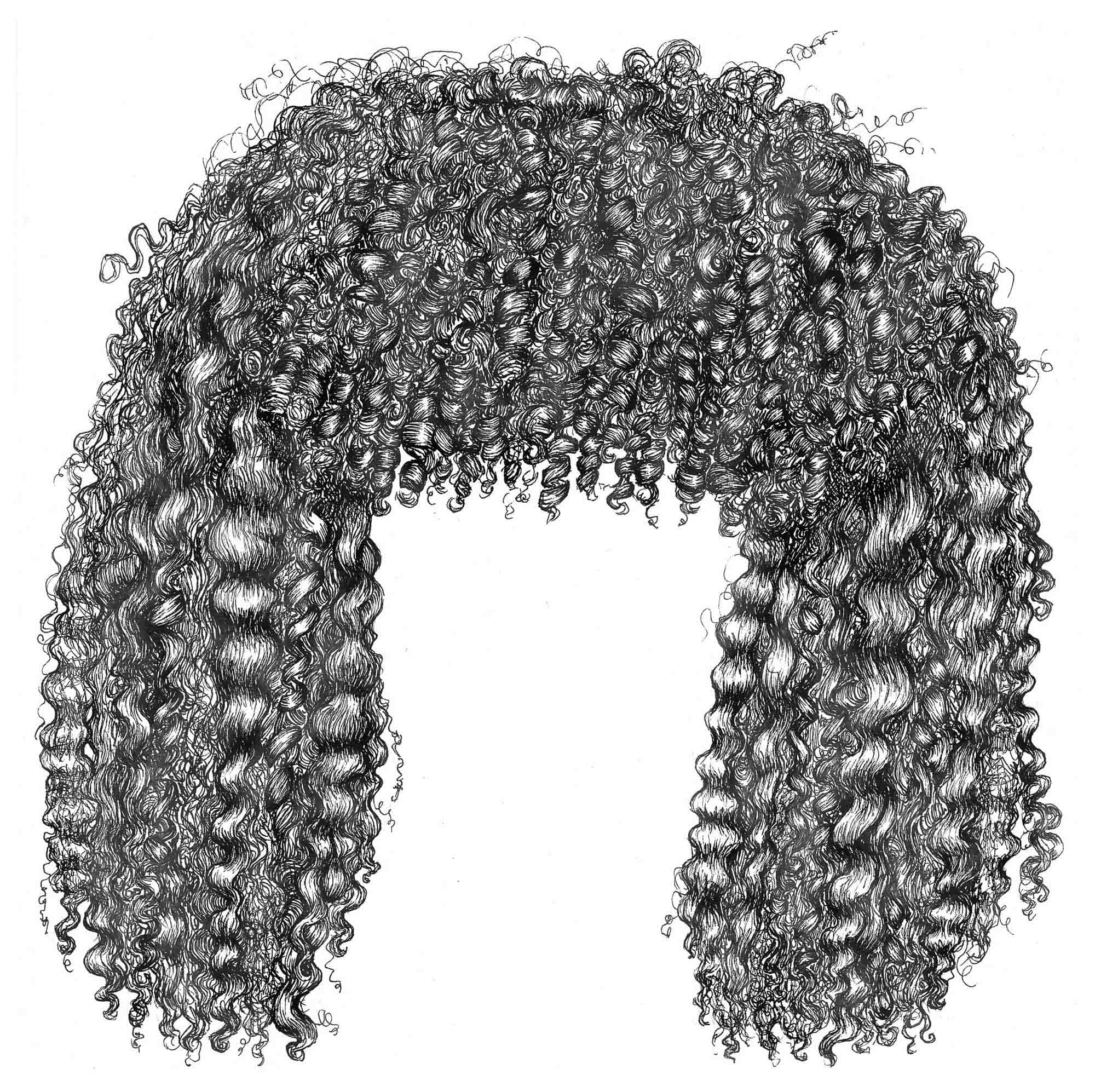

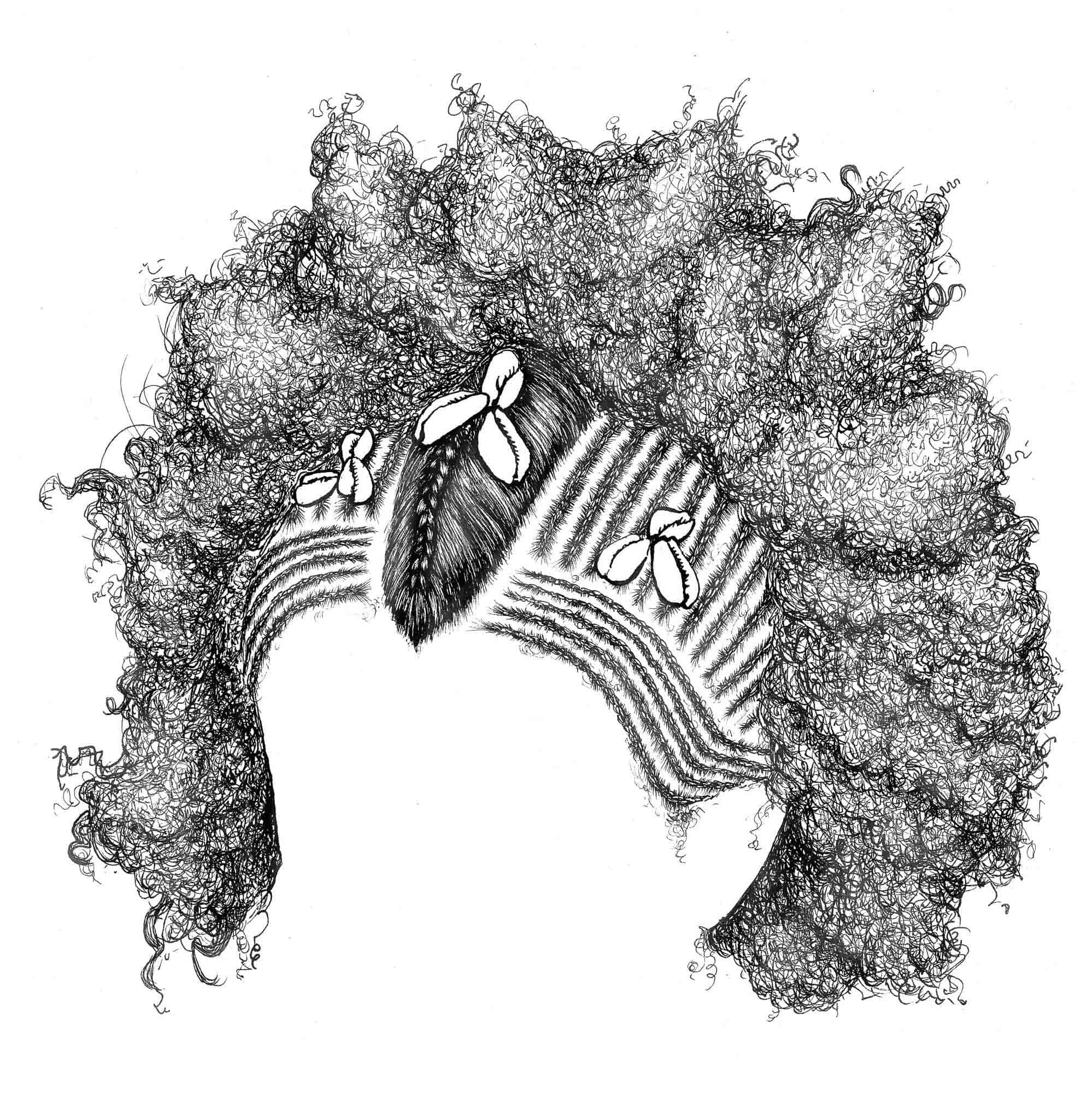

ART + CULTURE: Illustrator Habiba Nabisubi explains how her hair, health, race and art are all inextricably linked. Her experience of trichotillomania, the irresistible urge to pull out your hair, is both a curse and a blessing

Words + Images: Habiba Nabisubi

The community group BFRB UK is fundraising to become the UK & Ireland’s first BFRB charity. Donate now!

For resources and further reading visit:

TrichStop

The TLC Foundation for Body Focused Repetitive Behaviours

Black Minds Matter

Mind

The Awareness Centre

I have always had a complex relationship with my own hair, for several reasons. One is that I am a proudly dual heritage British-Ugandan woman: my mother is white British and my father is Black African. I grew up in both Kampala, Uganda and the UK, with my two older sisters keeping me grounded. Though there were some truly beautiful highlights, my childhood was turbulent. Being mixed-race (but perceived as Black) in the home counties during the early 00s was difficult. Even more so because we were fresh from Uganda (by way of Australia), which made us all the more ‘exotic’. Upon moving back to the UK in 2000, we were one of only two interracial families in our town. My sisters and I grew up putting on what we described as invisible armour just to feel able to go outside and face near daily microaggressions and othering. We existed in perpetual survival mode both in (due to our emotionally abusive father) and out of the home.

I always knew I wanted to be an illustrator—I think I was quite lucky in that sense. I was constantly drawing. I recognised from an early age that nothing brought me the same joy, and that despite the relocations, dysfunction, and change, drawing remained a constant in my life. It transported me to places beyond my house or town. Pure escapism—my imagination has always been a place of refuge. I truly believe that my ability to draw saved me from severe bullying. Nevertheless, I always felt some aspect of my mixed-race identity was up for public scrutiny, as Black bodies usually are, in predominantly white spaces.

The combination of moving to a place so starved of racial (and cultural) diversity and having racist ignorance projected onto me through to my adolescence definitely affected the relationship I had with myself. My beautiful hair quickly became the target for ridicule, which caused me to fall out of love with it for many years. Having to constantly explain, defend and legitimise my identity was draining and something I wish my younger self never had to do; I feel this is the sad reality for many people of colour growing up in sheltered pockets of the UK. I was 13 when I developed the hair focused mental health condition trichotillomania, though it took me two and a half years to summon the courage to Google my symptoms and discover its name. At the time I did not have the tools to comprehend what was happening to me, and succumbed to the condition in silence. Trichotillomania proceeded to compromise my mind for the remainder of my teens, further damaging my relationship with my hair, my mental health, and myself. Having and hiding the condition left me with deep emotional scars.

Trichotillomania (pronounced trik-o-till-o-may-nee-uh), also known as trich or TTM, is a Body Focused Repetitive Behaviour (BFRB) characterised by the often irresistible urge to pull out one’s hair, despite incessant attempts to stop or decrease the behaviour. The most common areas pulled from are the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes, though the pulling can be from anywhere on the body. In my case, it is my scalp. Trichotillomania is an under-researched and often very misunderstood condition that can interfere with one’s social, occupational, and emotional capacity to function. The condition can be painfully isolating and mentally debilitating to live with. I have had it for approximately 16 years.

Trichotillomania is not about disliking yourself or wanting to consciously purge your body of something that doesn’t belong. Nobody living with the condition will tell you that they’re pulling their hair out because they want to on a logical, cognitive level. It is not a form of self-harm—the harm is a consequence of the behaviour, but not its focus or objective. BFRBs are grooming behaviours, which all humans have and instinctively know when to stop. However, this ‘stop’ mechanism has been disrupted in people with BFRBs.

They/we cannot ’just stop’. Trichotillomania is a rewiring of your brain, and no one really knows why it develops. Childhood trauma is believed to play a role, but this is not universally the case. With trichotillomania, there are two types of hair pulling: both involve varying degrees of consciousness. These are called ‘automatic’ hair pulling and ‘focused’ hair pulling, and most people will do both. Automatic hair pulling usually takes place when one is engaged in passive activities such as reading, watching TV, studying, etc.—when the mind is generally elsewhere. Individuals will often disassociate and pull their hair out without fully realising that they are even doing it, which can be bizarre and feels scary.

Focused hair pulling holds one’s full attention and can feel extremely consuming. With this pulling, an individual feels building tension as the urge to pull grows (and your hand searches for the hair) only to be released (and feel relief / a dopamine release) upon pulling. But then once pulled, you feel crushing guilt, embarrassment, and shame. It can become a viciously dark and self-destructive cycle. For some individuals, the hair-pulling behaviours are manageable—an ebb and flow. For others they can grow more severe when feelings of stress, anxiety or depression are high, so they will pull their hair in a focused way to try to manage those strong emotions. It is a lot to manage and live with, especially alone and in silence.

Everyone’s trichotillomania experience is different. In 2013, I moved to South London to start my illustration degree. I was so excited finally to be able to flex my imagination, grow as an artist and individual, and simply be. In the cultural-melting-pot that is London, I knew I could turn up unapologetically. So, I did, invisible armour abandoned. Sadly, two weeks into my first term, I experienced an enormous trauma that completely obliterated my mental health and sense of self. I was diagnosed with PTSD and withdrew from my degree, my friends and what felt like my life for over six months. The stress of being unable to process the trauma alone caused me to engage in extreme amounts of focussed hair-pulling, which made me loathe myself. In a deep depression and exhausted by the weight of my trich, now exacerbated by my trauma, I decided to shave my head to try to regain the cognitive clarity and control I needed to heal.

I didn’t disclose the true reasoning behind my haircut to many people, as I was still internalising many demons and did not have the strength (or capacity) to educate others or explain myself. I let people draw their own conclusions. I was not prepared for the new attention my short hair and I received. Some people praised me for being ‘so cool’ or would tell me how lucky I was to be able to ‘pull it off,’ whereas others scolded me for cutting my hair off and couldn’t fathom why I would choose to do so. Everyone had an opinion, but no one had any idea of the extent to which I had, for years, tried to hide my trichotillomania.

These comments added another layer of pressure to my secrecy. Here in the West, hair loss is stigmatised. It is considered unattractive, a sign of poor health, malnutrition, illness, or full-blown ‘madness.’ It is quickly and cruelly judged, despite there being much more lived nuance than these horribly limited and negative assumptions. It pains me to see hair loss normalised to banter material and/or a punchline as it so often is. Hair loss is a broad spectrum and can be a highly personal, sensitive, and private process to go through. That privacy, however, is snatched away upon entering the public domain if you cannot hide your hair loss—your lack of hair makes you highly visible and open for scrutiny. We live in a world where so much of our individual value and self-worth is tied up in our hair. Hair is a navigational tool we all use to manoeuvre within and through society; it holds undeniable, albeit socially constructed, power. When it comes to hair loss and the individuals living with it, they/we are already at a disadvantage because they/we lack access to this ‘power.’ I hid my trichotillomania for so long because I was paranoid about what other people would think of me and how I would be judged. I became hypersensitive, terrified by the idea of further scrutiny.

The stigma attached to hair loss, and the lack of positive, authentic, honest representation and information about its intersection with mental health, meant that I buried my condition until it nearly broke me. In February of 2019, I shaved my head for a second time when I found myself once again consumed by my trich and searching for mental peace. But this time around I decided to disclose my condition via Instagram during Mental Health Awareness Week in May. This was not an easy or quick decision for me to make; I spent months talking and thinking it through with my therapist, building myself up to sharing my truth. And I am so glad I did: it remains the bravest and most radical thing I have ever done for myself. In doing so, I discovered the gargantuan power of vulnerability, and I haven’t looked back. That being said, I am still a work in progress. My journey with my hair and mental health has been long and is still ongoing but I am no longer hiding or in denial about who I am and where I’m at.

I’m not suggesting everyone living with trich should shave their head and start shouting publicly about their experience—though it might help—I simply want to use some of my story to help demystify this often misunderstood mental health condition.. We all need non-judgemental empathic conversations about hair loss in of all types, especially involving individuals with lived experience. There are so many people out there living with trichotillomania, quietly grappling with their impulses, isolating themselves and living with shame. To all of you, especially those of mixed-race/Black heritage: I see you, I am proud of you, and I implore you to be kind to yourself. You matter – don’t be afraid to take up space. How progressive it would be to live in a society that cared more about what is going on inside someone’s head, than what is growing (or not) on the outside.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR