- Hair Statements

- Hair Statements

- Hair Statements

ART + CULTURE: Photographer Juliana Kasumu reflects on her British-Nigerian identity and the less spoken narratives of West African heritage

Images: Juliana Kasumu

Interview: Emma de Clercq

Through her work, British-Nigerian photographer Juliana Kasumu explores contemporary issues relating to West African culture. Born in London, Kasumu’s interest in the subject stemmed from the desire for a greater and more comprehensive understanding of her African heritage, “a cultural history which was not taught in the schools I attended, or even easily accessible when conducting research”. She continues, “I attempt to bring attention to groups of first generation individuals like myself, often feeling out of place in the country they were born in, trying to make their way back to their motherland”.

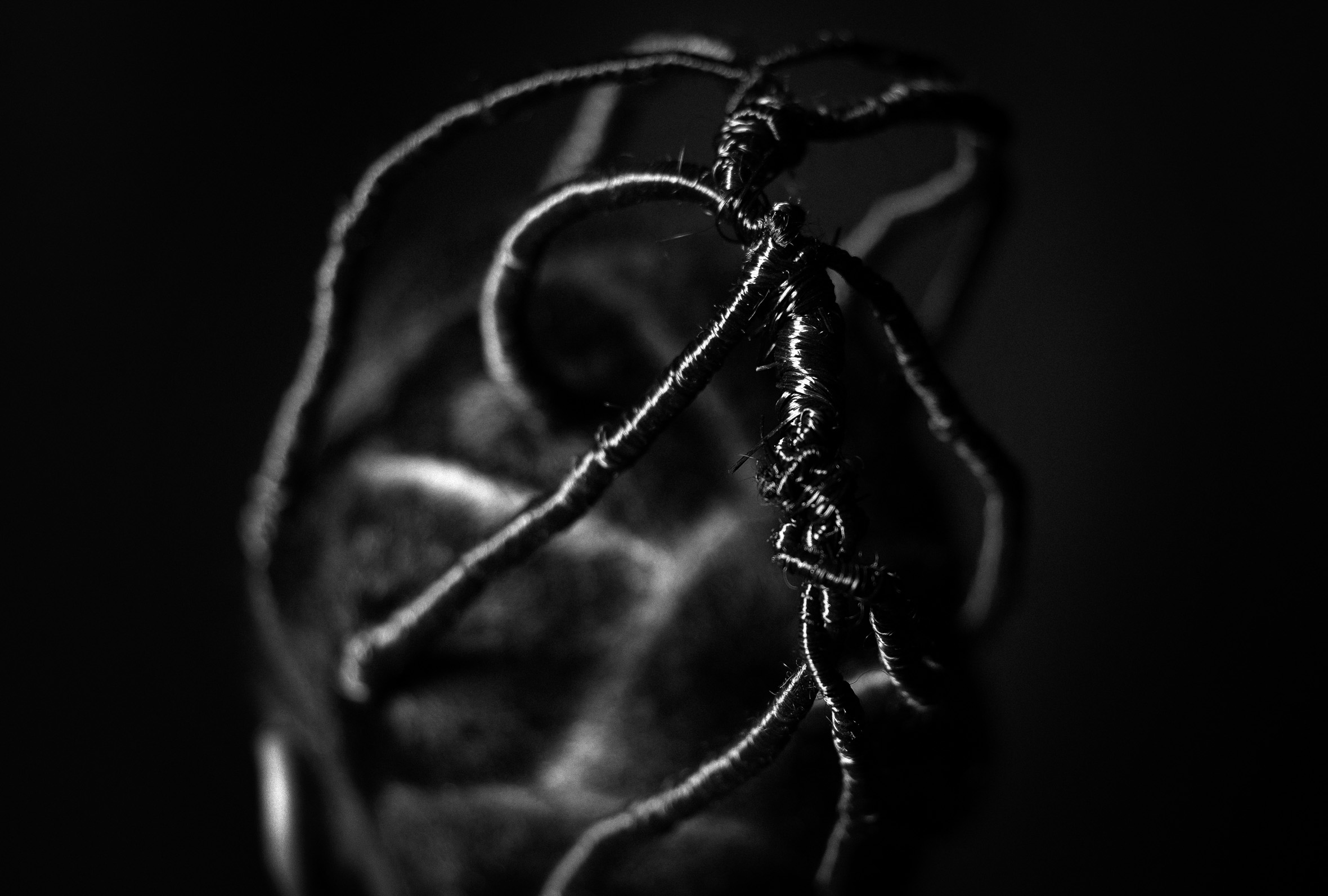

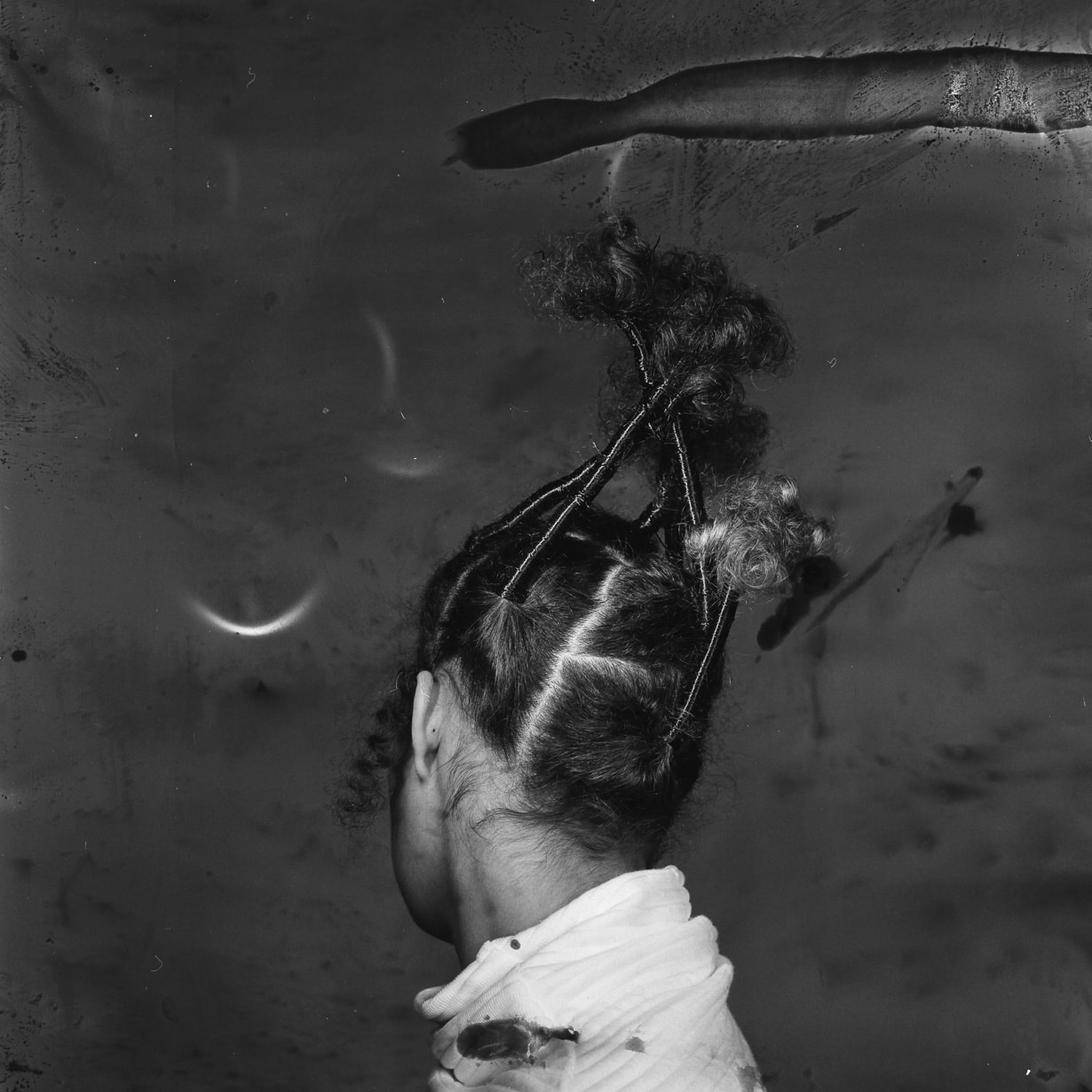

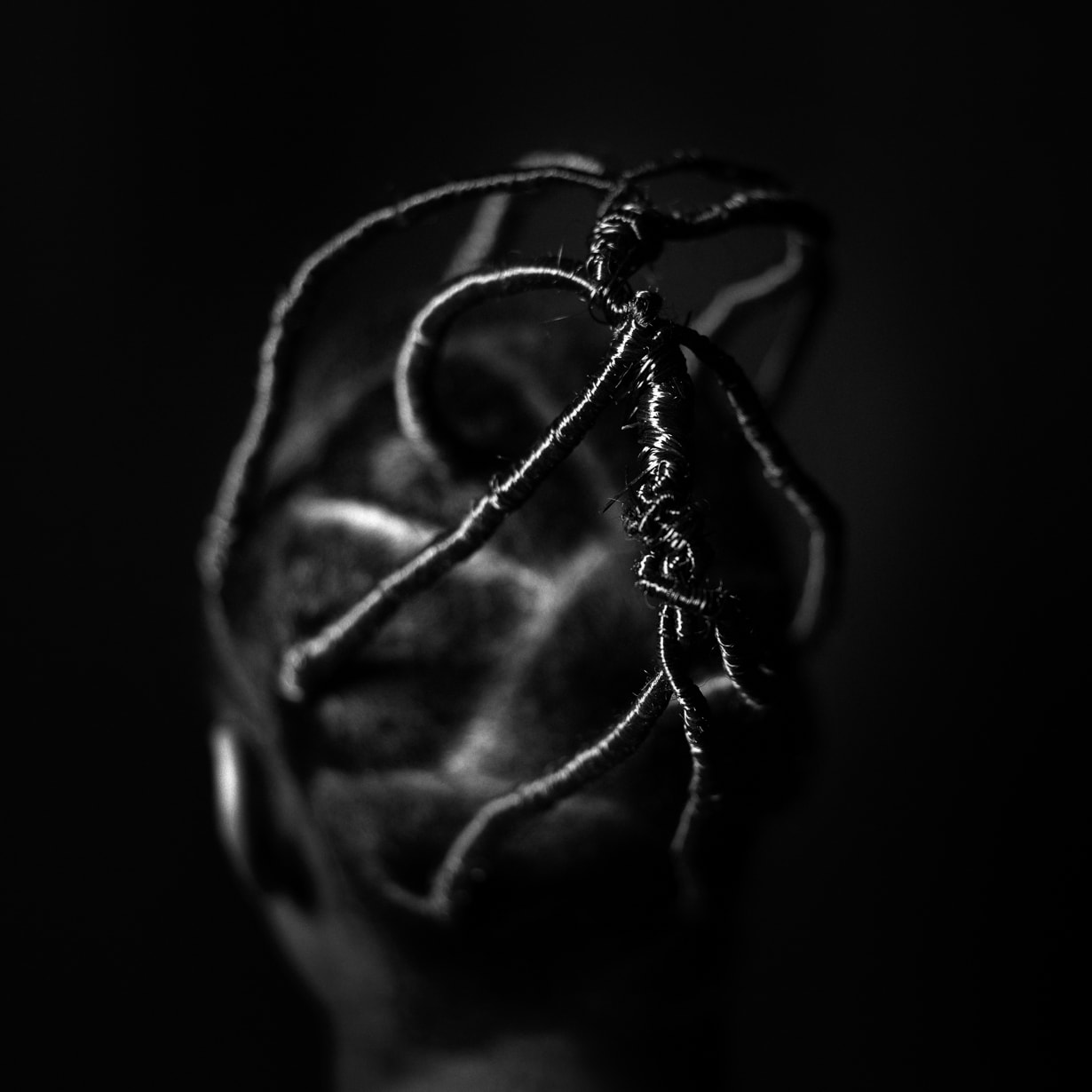

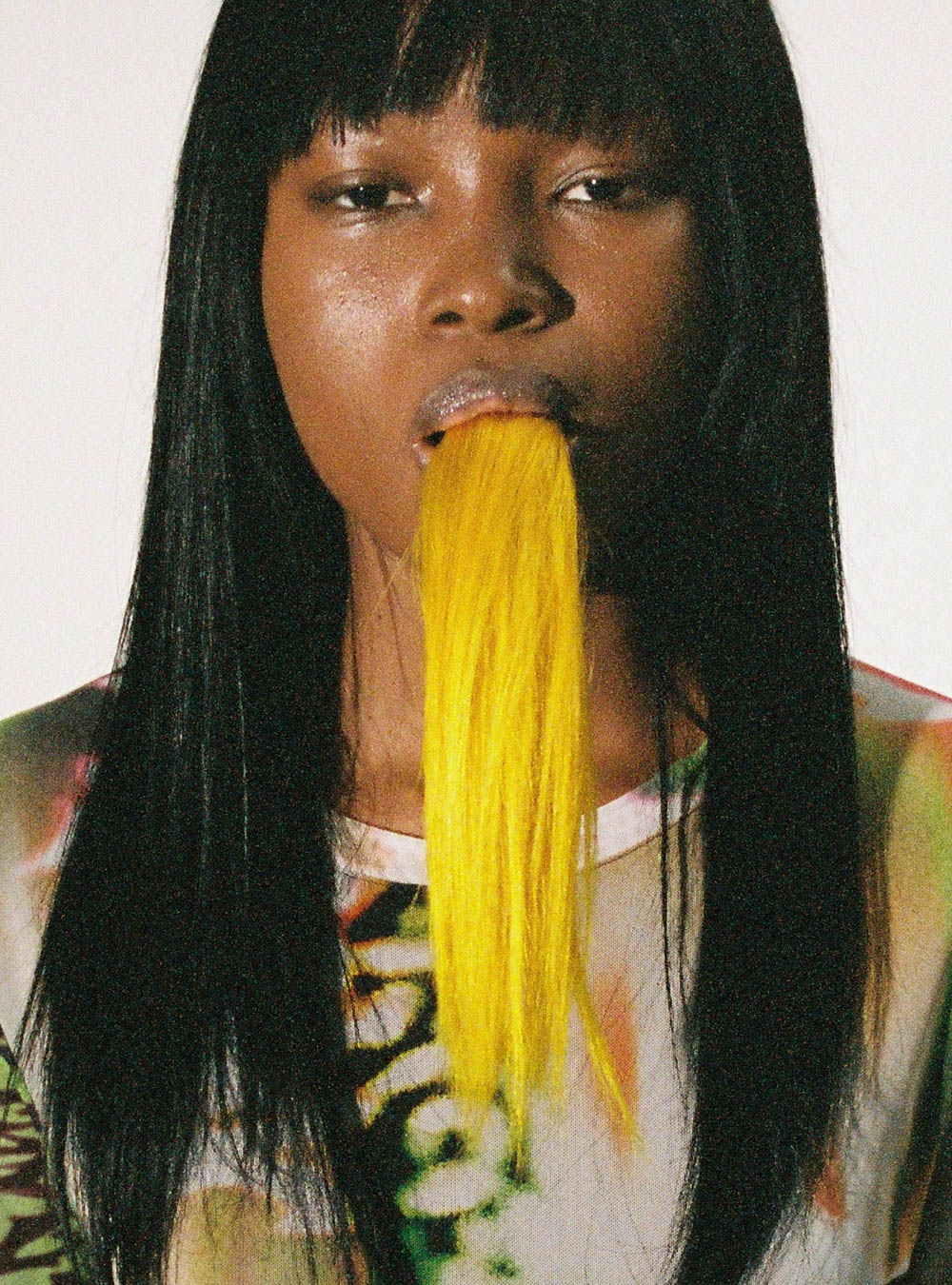

A recurring theme Kasumu explores is the relationship between African women and their hair. While undeniably beautiful, her work goes beyond documenting the aesthetics and unique intricacies of African hairstyles, but rather seeks to trace the political and cultural origins of these hair statements. She speaks of her drive to bring these often forgotten narratives to the forefront, and each of her projects is the result of extensive historical research. “Discovering how detrimental the effects of colonialism have been on the black woman and how she self-identifies, push me to do more” she explains.

Named after the distinctive style worn by women of the Yoruba tribe, Kasumu’s Irun Kiko series presents “modern renditions” of traditional African hairstyles, while examining “ways in which these women conform to, or rebel against Western ideals of beauty while reclaiming African heritage”.

From Moussor To Tignon: The Evolution of the Head-Tie explores the symbolism behind head wraps worn by women of colour. Investigating the origins of the head-tie in New Orleans, she reveals how this style statement in fact originated from a shocking act of oppression, as in 1786 Louisiana the law stated that “gens de couleur” (free women of mixed race) were required to cover their hair to distinguish themselves from white women.

How did you get into photography? I started off taking it at sixth form to fill in the time as I concentrated on other A-levels such as Psychology, but it ended up being the one which most challenged me. I had to think in a completely different way than I was used to. The last 2 years have been pivotal to the direction of my photography. The decision to refocus my photography on my identity as a British-Nigerian, femininity and the less spoken narratives of West African heritage, remains my motivation to keep pushing.

Who are some of the artists who inspire your practice? I always revisit Carrie Mae Weems and her unforgettable Kitchen Table series. I sometimes mediate on it as a reminder to keep portraying the stories of black women, keep portraying stories of myself. Because who better to tell my truth, than me? Other late greats, such as Seydou Keïta , Malick Sidibé, Irving Penn and Robert Mapplethorpe, photographers who I consider to be visionaries in merging of art and fashion.

What does your own hair mean to you? Has its meaning changed since you began exploring the subject? Most definitely, without a doubt. Honestly, this all started out of curiosity for my own hair in its natural state, without chemicals. I was going through a stage of trying to understand who I truly was as an individual and the conversation of double-consciousness as a British-Nigerian came into play. I became so obsessed with my hair and questions of identity; eventually stumbling upon all this history about West African hair methods. Discovering how detrimental the effects of colonialism have been on the black woman and how she self-identifies, push me to do more. Once I gained an understanding of who I am, what my truth is, only then could I begin to heal the internalised self-hatred I had once experienced.

What’s up next? I feel that the cross-over with all of these projects is never-ending. I still have so much I need to explore, uncover, historical research that needs to be done. Expanding the conversation on hair and identity, opening it up for further investigation, is something that I feel will never end for me. This is such a universally relatable topic, and I feel like I have only just touched the surface.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR