- Domestic Hair Permeations

- Domestic Hair Permeations

- Domestic Hair Permeations

ART + CULTURE: Jessica Wohl’s installations create an eerie sense of life: “Whether in a stairwell, on a bed or a chair, the inclusion of hair in the work implies that there’s something alive within that structure.”

Interview: Alex Mascolo

Images: Jessica Wohl

In her most ambitious hair-themed installation to date, Tennessee-based artist Jessica Wohl covered the stairs of an abandoned Arkansas hotel in synthetic hair, cascading down the steps like water. Continuing to build on this idea, she later created eerie domestic set-ups containing disembodied pools of hair. Discussing the inspiration behind these projects, Wohl explains, “long hair implies growth, so whether in a stairwell, on a bed or a chair, the inclusion of hair in the work implies that there’s something alive within that structure”. With these sculptures she playfully acknowledge the dual connotations of hair. Depending on the context in which it is found, this same fibre can quickly transform from being desirable into something frightening or repulsive.

“I use hair to imply a kind of beating-pulse left in what would normally be considered an inanimate object or space.”

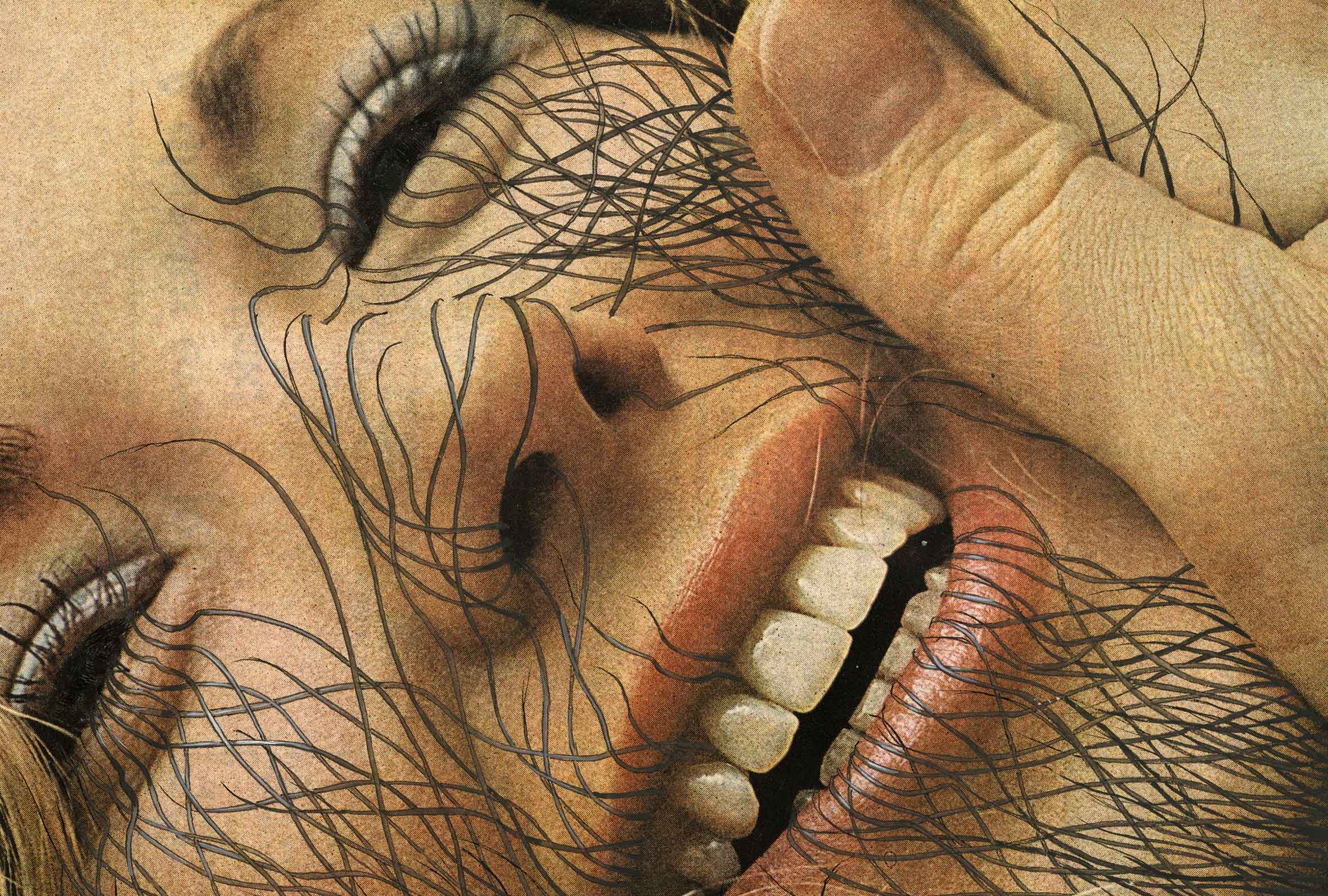

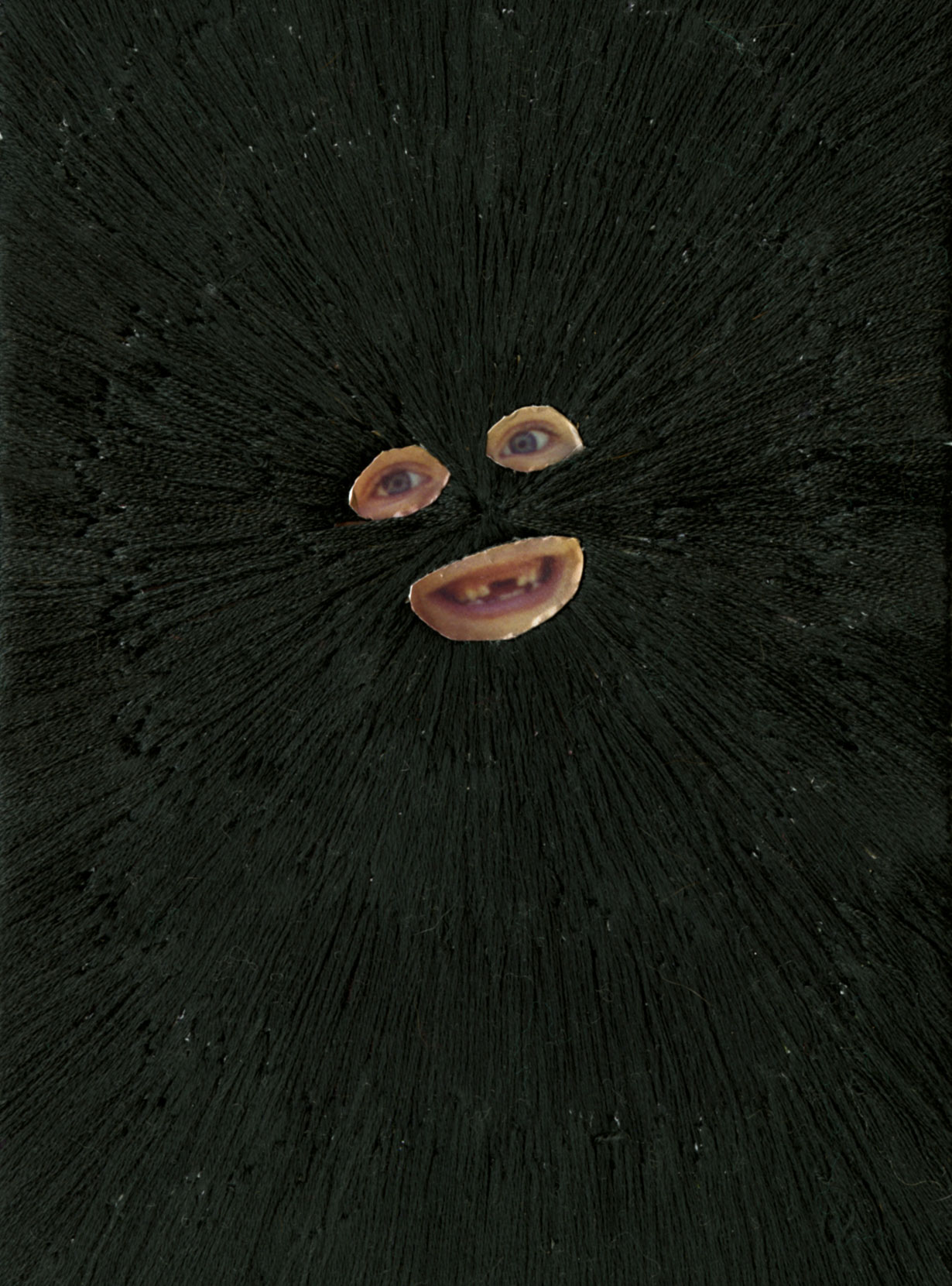

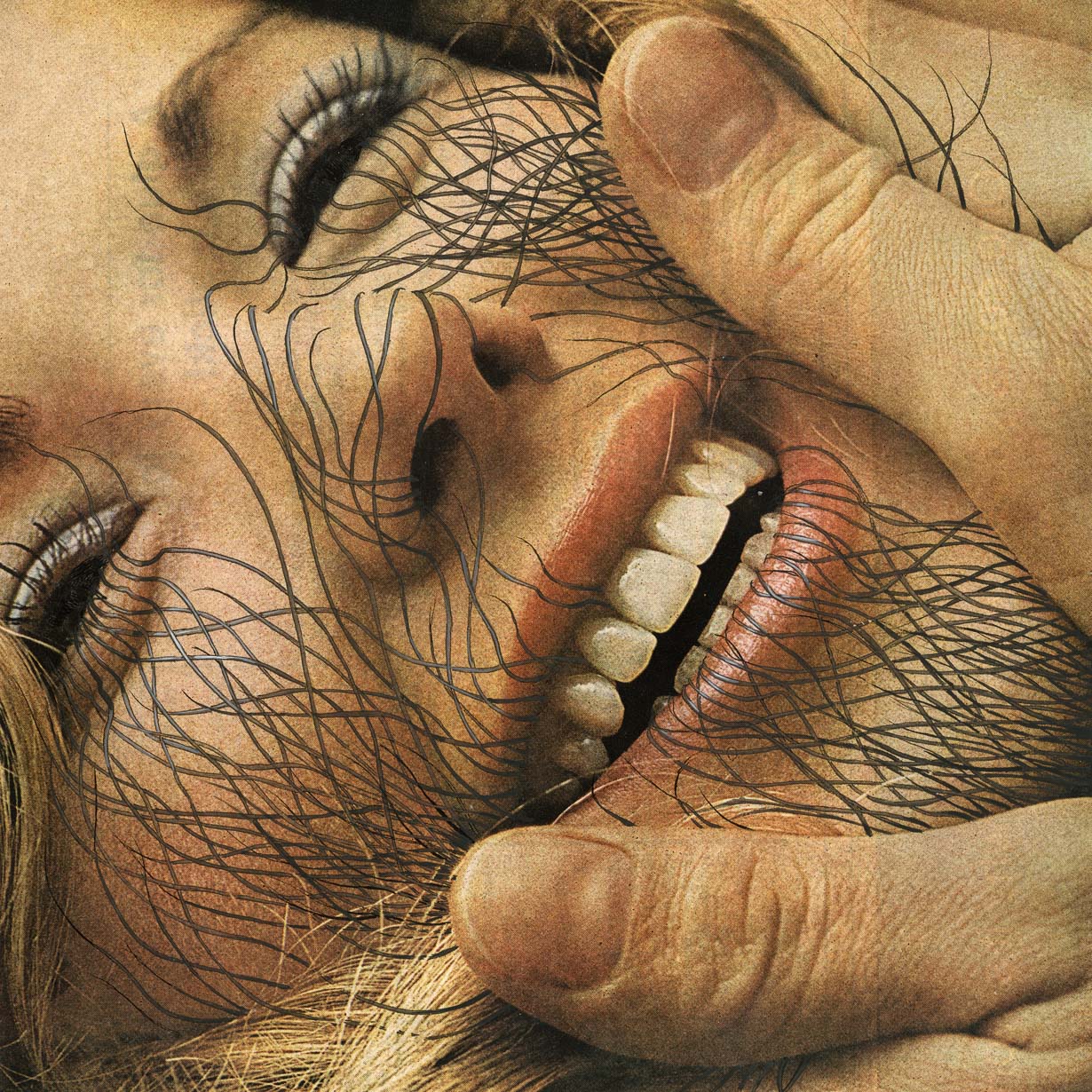

Hair is also suggested in Wohl’s collages, in which she alters existing images through drawing or sewing. By concealing the faces of her subjects in multiple layers of thread or drawn lines, they are imbued with a strange, animalistic quality. However, she explains that her main interest with these works is to explore ideas surrounding masking, self-image and control. We spoke to Wohl about her multi-media practice, and the role that hair plays within it.

What draws you to hair as a material? I’m drawn to the tactile qualities of hair; it’s both soft and shiny, it recalls a tenderness and intimacy when it’s handled, and yet, when hair is removed from the head, it ceases to be associated with beauty and begins to be associated with something dark, mysterious, uncanny and off-putting. I enjoy those dualities and try to exploit those contradictions in my work.

Could you tell us about your installation Mountainaire Hotel?In Mountainaire Hotel, my work was installed at a hotel of the same name, that had been abandoned for 20 years. The hotel was opened up for two days for installations, and I liked thinking that the building had actually been alive the entire time it was abandoned, as if it had been growing hair for the last 20 years. This device also creates a sense of mystery, fear and uncertainty, akin to what one might feel in a haunted house.

Following the installation at the Mountainaire Hotel, I continued exploring this phenomenon within a domestic setting. I became fascinated with work that revealed an energetic residue of the lives lived within a space, and in the absence of a living person, began to imbue the works with an ‘implied life’, introducing the idea that somewhere within this space, whether it be in the walls, the bed or the chairs, was alive. The works also create confusion regarding time and place. The antique furniture, white sheets and toile wallpaper leave the time period of this home unclear, implying that this space may have been sitting abandoned for centuries, decades, years or days. It also leaves the place unclear; while a Western style is implied, the class and the location of the home remain unidentified. These unanswered questions can help create uneasiness, hesitation and intrigue in the viewer.

In your drawings you use thread and pen to partially obscure faces, making the subjects appear almost animalistic. Was this the intention? I love the interpretation of ‘animalistic’ here, but actually I had other intentions with these works. The Sewn Drawings explore the space between how we present ourselves to others and how we feel about ourselves privately, in our own heads. We tend to associate a photograph with reality, so a posed portrait in and of itself is a strange phenomenon as it documents a moment of our ‘happiness’, and yet, it is so staged. On the other hand, when we see a mask of actual thread sewn onto the photograph, our sense of reality is upended, as suddenly, next to the real dimensional thread, the photograph becomes a mirage; merely a piece of paper with emulsion and an exposure. So, which is more real, the mask we wear in public (the thread) or the person we are beneath it (the posed photograph)?

The Magazine Drawings, while aesthetically similar, address a different issue completely. Working again with a face covering, these drawings depict a foreign entity taking over a woman’s body. Much like the Stepford Wives, who’s husbands fear their wives’ independence, these women are being subjected to a dark force beyond their control. They either smile through it to even have a hope of surviving, or perhaps they are oblivious to it occurring at all. Taken from advertisements from the 60s – 80s, these works recall a time where women were enjoying their liberation, and yet, they were simultaneously portrayed in the media as submissive, sexual objects for men’s pleasure. Today, these works recall our current political climate here in America where men make decisions about women’s bodies as a way of exerting control over them; it’s just that now the location has generally moved away from the domestic space and occurs now within the intangible world of policy making.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR