ART+CULTURE: Anouska Samms is the artist delving into mother-daughter relations by creating ceramics and tapestry out of hair

Artworks + Photography: Anouska Samms

Artist’s Statement: Anouska Samms

Interview: Katharina Lina

When the London-based artist isn’t working as a social and communities researcher, Anouska Samms can be found scouring the city for freshly cut human hair. Having grown up with a curly red mane, hair has always played a significant role in her life, home and identity, but now Samms is utilising different forms of media to deliberately examine hair, and the maternal relationships orbiting it.

Artist’s statement: Mitochondrial DNA within the hair shaft is passed from a mother to her children. In the work of Anouska Samms, hair is used as a symbolic lens to reveal and interpret the tensions and bonds of maternal relationships. Where intricate patterns of hair are knitted, woven, sewn, sculpted, filmed – a maternal bloodline, and the female rituals born from its lived relationships, are playfully examined as a way to uncover humorous, yet loving and even obsessive traits of intergenerational mother and daughter connection.

Mothers and daughters in Samms’ family have passed down unconsciously, yet unquestioned (until now) ‘rituals’ whereby the women dye their hair red. As fate would have it, Samms was born ginger. Yet the chopping and changing of the individual identities of five generations of mothers simultaneously demonstrates a (seemingly accidental) inheritance and collective identity beyond DNA.

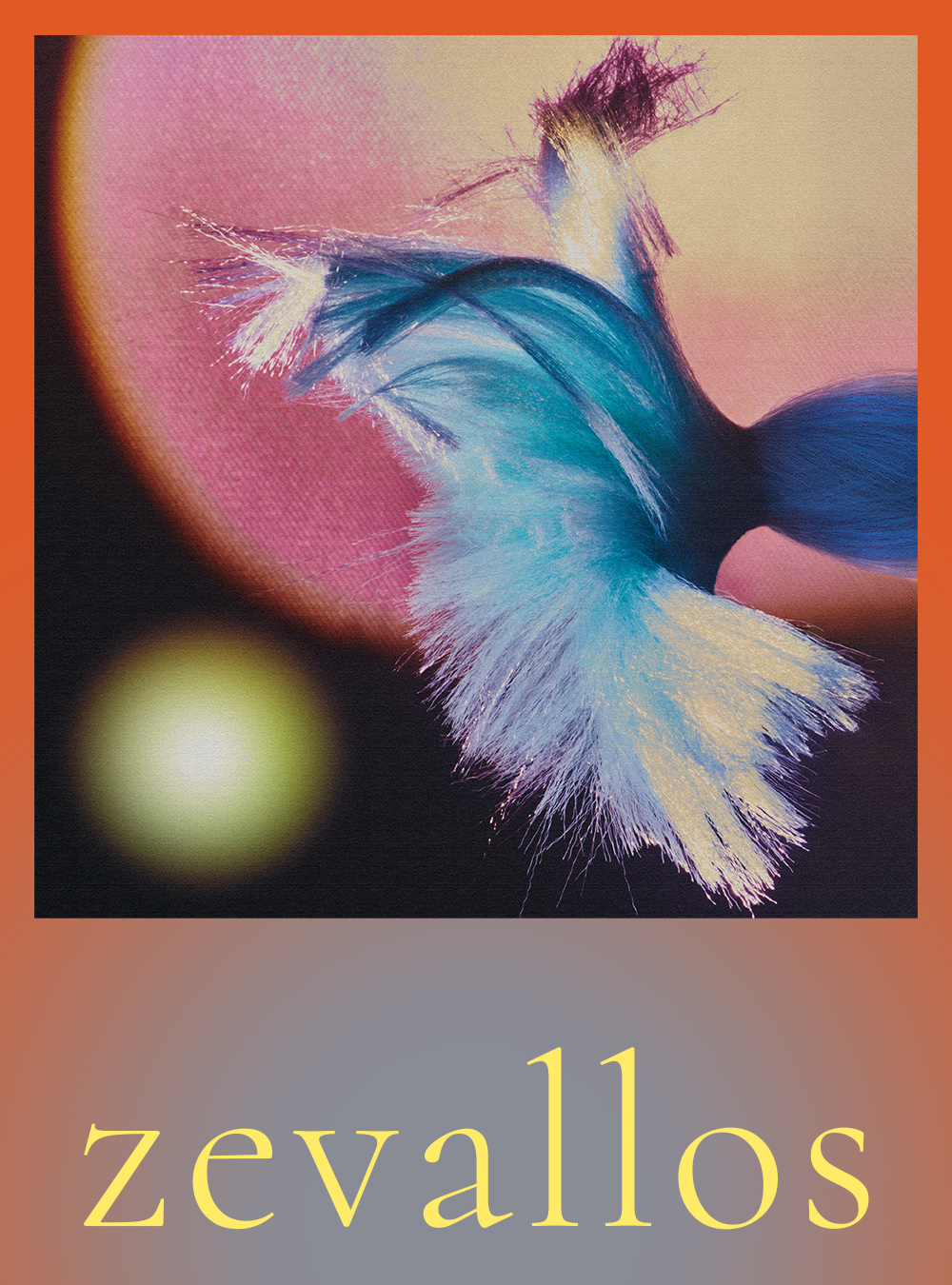

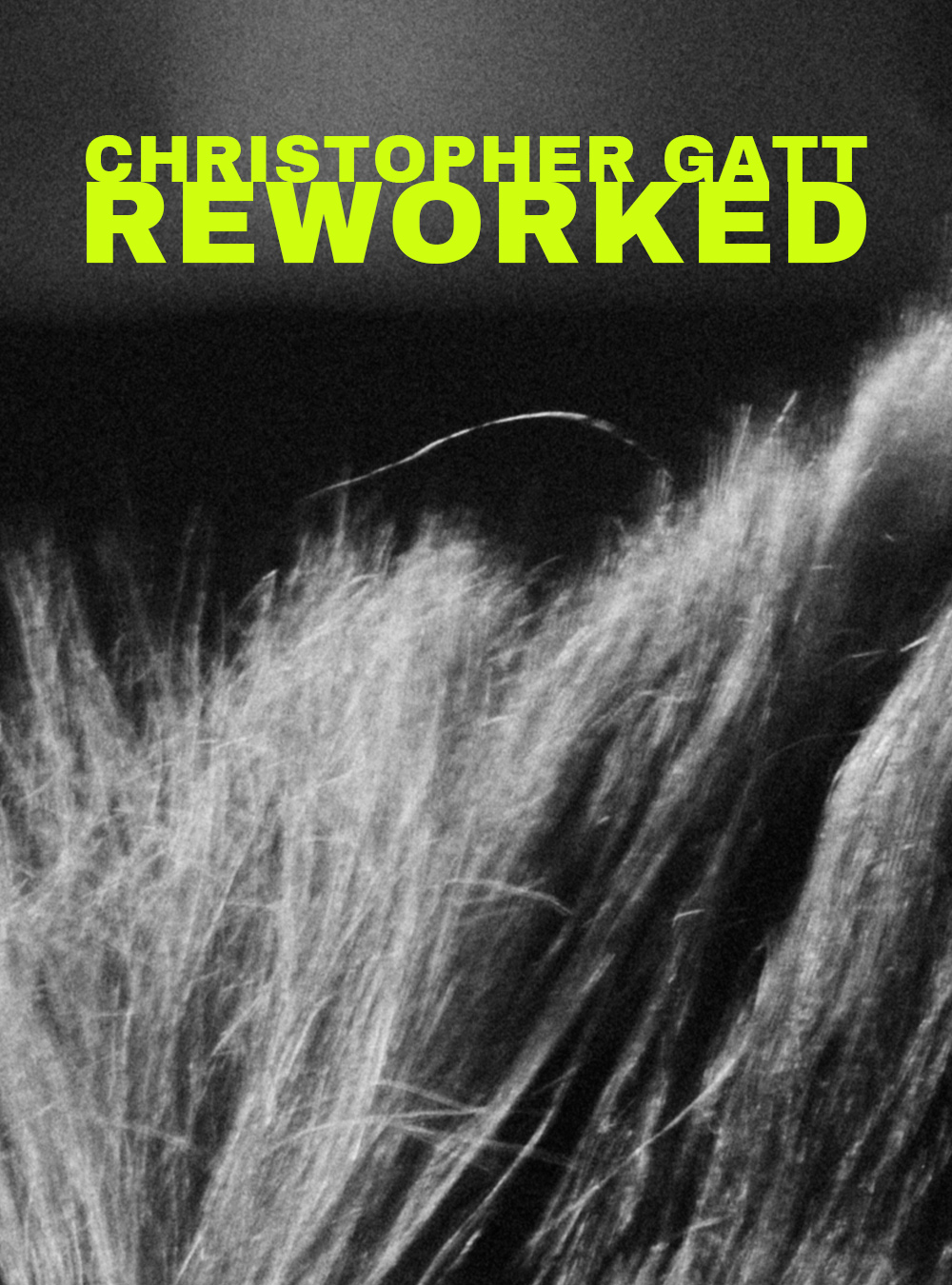

This body of work encompasses film, tapestries and ceramics. Clay is often incorporated with the hair. Both materials are humble, organic – serving a natural purpose that is richly symbolic. The common cultural association of pottery is its role as an artefact of bygone eras, its durability, history, maintaining parts of its form and design against the effects of time. Notoriously regarded as ‘women’s work’, domestic handicrafts are also used through practices of embroidery and by weaving on large floor looms. These provoke the obvious ideas of femininity, tradition, storytelling and entanglements. However within this work the familiar or the expected outcomes are flipped, and instead what is offered is often distorted. Vases are morphed into unstable vessels, tapestries are loose and fluffy and in places incomplete. Appearing both joyful and bizarre, the delicate and ornate details of the work are subverted by the presence of the abject in the use of disembodied human hair – a tongue-in-cheek way of representing both the purity and absurdity of mother and daughter exchange. Here the impermanent qualities of memory, materiality and motherhood are examined as a form of visual folklore.

Hair is supposedly symbolic of your nature. Ours is no less so, though you might call it artificial.

How did your creativity manifest itself when you were younger? When I was a child I used to try and dye my barbie dolls’ hair ginger. It never worked. And in some ways the work I make now is a ‘grown-up’ form of that. A few years ago I was doing a textile course for fun, and I decided to use some of the techniques I had been taught on different materials that I had at home – one of them was my hair. Having been raised by two women – my mother and my grandmother – I think the most meaningful thing for me that kept showing up in my work at that time; was what it meant to be a daughter in such a unique relationship of three women, and the unconscious ways that being a daughter manifests itself in my own life. Such as through our ginger hair.

Someone once said to me that in your practice, if there is something that you instinctively repeat or are drawn to, something that you find yourself constantly doing, then that’s your thing. That’s something that wants to be played with and explored further. I think that rings true for me. The ‘theory’ or message is always there, it’s always in the play or the material forms. Just because that meaning is not what you may initially start with, doesn’t mean it’s not there. It’s there. Like small acts of creativity that we perform all the time without knowing it. So even when I was a child, the traditions of hair, playing with my Barbies, my mother tinting her hair etc., and me using hair then and now, it says so much more – I suppose it was and still is about family, bonds of repression and obsession and care.

What is your relationship with your own hair like? Has your hair always been a subject of interest to you? I guess it’s been an interest to others, so then it became more of a thing for me around my own image. I was often teased for having massive ginger hair at school — it was a bold look for a 13-year-old as it wasn’t particularly styled. And when I was 4 years old, a teacher asked my mother if she could cut my hair because it was so ‘unruly,’ telling her that ‘I never seemed to look tidy’. Being the fiery and assertive woman that my mother is, she reported the teacher, and my hair remained intact.

So I was always ‘defined’ or described by my hair, but quite often in a loving or cheeky way. However when you’re a self-conscious teenager who is growing as a person in the most awkward of ways, the last thing you want is to stand out for your appearance — and I probably did. Even though I come from a long maternal line of redheads, I didn’t really consciously associate my own identity or my relationship with my hair with my relationships with the women in my family. That seems incredibly bizarre, as it is surely something so obvious, but perhaps because it was so close to me I didn’t really take much notice of it until only a few years ago.

How has dying the hair red become a ritual passed down from mother to daughter in your family? What does red hair encompass for you in terms of identity? So this is when I get a bit embarrassed. As I previously mentioned, I come from a long maternal line of redheads going back 5 generations. However I am the only natural redhead — and even now I boost the colour with red hair dye. There is a joke in our family that the red dye seeped into my DNA, so much so that I was born with bright red strawberry blonde hair. All the other women, the mothers and daughters of the family, dyed or dye their hair red. And I unconsciously started to do the same, making my hair a bit darker. Like a strange form of mother-imitation, where we probably need to all do a lot of soul-searching to understand what it means for us all as individuals. Yet at the same time, it’s like an unspoken ritual in our family that asserts the strength, closeness and fierceness of the women that hold it together, even if at times they haven’t all got on.

It’s ironic that everyone seemed to be so oblivious to such a bold statement, but they were nonetheless. When I ask my grandmother if she was actively trying to look like her mother she said no, she just ‘liked the colour’, and thought that it suited her. The same goes for my mother.

When I realised the ways in which I was unintentionally adding to this quite beautiful, yet certainly creepy legacy, I was definitely a bit repelled by it. The cherub backdrop in the photograph with 7 of my hair pots/vessels altogether was originally used in a film I’m making called It’s not perverse, it’s mothers. So take from that title what you will!

Whose hair has been used in these works? Is it all from the women in your family? Yes, but also a total variety from across London. I’m currently working on a film and huge tapestry, which means I need a lot more hair. So I make desperate pleas on my instagram account for hair from friends and anyone who will listen. When friends get their hair cut, they ask their hairdressers to save them their hair so that they can give it to me. I imagine that this leads to an awkward conversation about their strange friend Anouska. But when those conversations go well, I end up getting follows online from lots of lovely hairdressers who are so generous, as they kindly ask their clients to give me their chopped off locks for my art. While on the whole my work is about using real hair, some of the pieces use synthetic hair where I wasn’t able to accurately trace its original source to ensure that it was obtained ethically.

What was the process of working with hair like? How did you overcome challenges that came with mixing hair with more traditional media? Overall it’s quite a long process from sourcing the hair ethically, to tying it into bunches so that it is easy to bleach, dry, colour, wash in my bath, then dry again, then re-bunch — all before I can begin to sew onto it, knit it, and then either mould it into a textile first, or just shape it immediately using clay to make it into a solid vessel. Sometimes just preparing the hair alone can take me a couple of days.

As a material, I do find it challenging to use, as I’m figuring out on my own how best to work with it. There’s certainly been a lot of trial and error. But one thing that has stuck with me from when I was little is putting unusual things together, and seeking pleasure in making when things supposedly go ‘wrong’. As much as I plan and sketch out my ideas, I like it when new and unexpected things happen. I am in awe of victorian mourning jewellery and the specialised skills around labouring over fine and resilient strands of hair, and also wig makers. In spite of the challenges that hair may bring with it, when something doesn’t go to plan, something else presents itself which I perhaps wouldn’t have thought of otherwise – and I find that so playful. However, not clogging up my sewing machine is most definitely an ongoing challenge.

Has creating this series of works exploring mother-daughter relationships had any impact or revealed new perspectives on your own relationship with your mother? Through this work I’ve understood more about daughterhood. When I started to unpack what my playing and experimentation with hair meant to me, I thought more about the role of the daughter in contemporary culture. We are all familiar with the contradictory cultural associations of motherhood, both its simultaneous pain and beauty, obligation and joy. These experiences are tied to the experience of daughterhood in my own family, but culturally I’m still unsure about the degrees to which these are understood in the mainstream.

As with colouring my hair, working with hair in my own work was also something unconscious and unplanned for me. If I’m honest I find that a bit unnerving and simultaneously fascinating — what becomes part of our identity and personal rituals without our awareness. Although I would say I’m an open person at times, personal work isn’t something that I ever thought I would want to make. My strong relationships with the women who raised me would be the last things I would ever want to explore in this way. I find it really difficult because to explore the meaning or intention behind something you can’t be superficial about it. There needs to be a degree of honesty, and with honesty often comes things you don’t want to face, let alone share with others. But as I said before, it was all that I seemed to be making.

In terms of new perspectives, I’ve allowed myself to learn more about the moments at which the direction of feeding changes, or the moments at which they are inextricably linked. Or quite simply the moments when I’ve just been a little bitch, and can do better. But the overwhelming feeling of what a unique trio we make is something that has always remained.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR